Bordoli/Fagan

The Narcissistic Fish

Programme

KINDLY SUPPORTED BY SCOTTISH OPERA EMERGING ARTISTS BENEFACTORS, SCOTTISH OPERA’S NEW COMMISSIONS CIRCLE & IDLEWILD TRUST

Each has their own frustrations – but will they reach boiling point?

Creative Team

Composer

Samuel Bordoli

Libretto

Jenni Fagan

Director

Antonia Bain

Cast

Belle

Charlie Drummond*

Angus

Arthur Bruce**

Kai

Mark Nathan*

* Scottish Opera Emerging Artist 2019/20

** The Robertson Trust Scottish Opera Emerging Artist 2019/20

Synopsis

Chef brothers Kai and Angus battle with each other about whether they should visit their dying father in hospital, but it’s the start of a busy shift in the kitchen of Angus’s restaurant, The Narcissistic Fish.

Caught in the middle is Belle, the brains and talent behind the business, but also the least well paid of the trio.

When a phone call confirms the death of the brothers’ father, Kai is angry that they’ve left it too late to see him, but Angus seems more interested in what they will inherit.

Tension builds into the evening as Belle and Kai share jokes at Angus’s expense. They argue over whose idea it was to open the restaurant.

Belle tries to confront Angus about his actions. His lack of remorse prompts her to walk out. Kai tries to stop her, and the brothers then begin to fight.

Belle explains her dilemma: she is pregnant, and has to make a decision about what to do about her baby. Kai tries to console himself about his brother’s lack of conscience.

Tensions simmer down and all three return to work.

When the restaurant closes, they share a beer. Angus offers Belle a pay rise and says he will make her a partner in the business – although he won’t acknowledge her publicly for a few years.

Angus and Kai leave Belle to make her final decision – to leave The Narcissistic Fish, and to raise her child free from the mistakes of the past.

Words and Music

Composer Samuel Bordoli and librettist Jenni Fagan reveal how they went about creating The Narcissistic Fish.

Where did the idea for an opera film originally come from?

Samuel Bordoli: I’ve been Scottish Opera’s Composer in Residence since 2017, and I was discussing the idea of some kind of multimedia production with the Company’s General Director Alex Reedijk. It was a very open brief: he just asked me to go away and think about what it might be. I realised that I didn’t want it to be any kind of video installation, but probably as close to a performance as possible. Then I started talking to Antonia Bain, who’s the Company’s Digital Content Producer and also a film director, and we worked together on that concept. We wanted to make a film that happened to be an opera, not a film of an opera.

How did you come up with the early ideas for the setting and storyline?

SB: Antonia and I initially had in mind a completely different scenario, which we were working on without any librettist. But I went off that original idea and suggested a kitchen setting, which Antonia also really liked. We then spoke to Jenni Fagan about the concept and asked her to think about the specifics of narrative and characters. And she put a lot of work into that – I think the end result works really well, and it was great to work with her. We knew there would be three singers because of practical constraints, and three characters seemed like a solid number too.

Jenni Fagan: Antonia and Sam had several early ideas they were keen on, and one was working in a kitchen. I loved the idea of being able to use the sound of steam, or a pot boiling, or a knife chopping to punctuate that world. I wanted to write something that felt relevant to today, and so I chose a hipster restaurant run by two young brothers who are making quite a name for themselves. One of the brothers is very narcissistic, and the other is coming to the end of his lifelong journey of both tolerating his older brother and compensating for his sibling’s lack of empathy and insight. The female character is actually the real talent behind the restaurant, and she’s been completely overlooked and taken for granted. She’s fighting back in less obvious ways. Each character has something to lose.

Turning to you, Jenni: you’ve written novels and poetry, as well as essays, screenplays and short stories, but this is your first opera libretto. Why did you feel compelled to work in opera?

JF: I was interested in writing an opera libretto that didn’t necessarily follow expectations of the form. Opera can sometimes feel like an exclusionary, elitist medium. I wanted to write interesting, working-class, tattooed, flawed, Scottish-speaking characters and have them battle out their dynamic via these huge operatic voices.

How did you find writing the libretto drew on your previous writing experiences?

JF: All of my writing has a similar ethic, in that I will go as far as I have to, in order to create something authentic and unique to itself. I try not to repeat the same stories over and over, but to create stand-alone works that have their own identity. I drew on my script-writing experience, song-writing skills, poetry and literature – they all had something to offer.

Did you find that creating text for an opera libretto was different from texts for poetry, novels or plays?

JF: There’s a specific need to consider voice in opera that’s different to the way I approach voice in literature. The notes will elongate any sentence, the poetics must not be too ornate (for my taste), and the story must be concise. I don’t think there’s space to digress endlessly when people are singing an aria.

How much did the kitchen setting influence your ideas, do you think?

JF: Sets or locations are something I very much enjoy creating, so I wanted to design a loft-type restaurant with an open, industrial-style kitchen but take it off key – perhaps the kitchen could be in the underworld, or it might have a nod to Twin Peaks just because of the lighting. Playing with that was a good way to create atmosphere and tell us a lot more about each character.

What was the relationship between the film’s storyboard, the score and the libretto? Which came first?

SB: I think the storyboard came first, but it was a very collaborative process, up to the point where I had to start writing notes on manuscript paper. Antonia obviously led the storyboarding, and we were then led by Jenni’s libretto, which she adapted somewhat because of the demands of setting it to music. But that’s probably the most normal part of the process – it’s what would happen anyway between a librettist and a composer.

Jenni: how did you find the process of collaborating with Sam, and of sharing ideas between the two of you?

JF: I was left to rewrite and finalise the text, with a few meetings to give me feedback on individual drafts. Sam had questions about the pronunciation of certain Scots words, also character development on earlier ideas – he felt at one point that my brothers were a little too dark, for instance. I pulled the story apart and put it back together a few times. I do that with everything I write. Sam most enjoyed how I write as a poet, so I was happy to write the libretto as if it were a poem. I write everything as if it’s a poem, to be honest, even if it’s only apparent to me. The final version is very close to my original text: making the changes was more a process of refining the story and allowing each character to stand out and have their own journey.

Turning back to you, Sam: did the kitchen setting give you immediate ideas for the opera’s sound world?

SB: I had some vague ideas, yes, mainly about instrumentation. It seemed like a good opportunity to play around with the kitchen setting – pots and pans, food processors and other things. As I did more work on the score, I decided they would start real but then become more integrated into the score to that they almost became musical instruments, and some of them have ended up so heavily processed that you wouldn’t know where their original sound came from. The other instruments you hear are all actually processed real instruments, manipulated strings and winds. It’s mostly an electronic score. We couldn’t use real musicians because all of this work was done during the lockdown, so I ended up using virtual instruments. The only thing I planned early on is to do with tempo in the first half of the opera. The tempo is indicated by a kitchen implement – a knife sharpening and other things. When the next tempo comes in, it forms a cross-rhythm over the top of the first rhythm and then becomes the new beat. It modulates rhythmically three times during the course of the piece.

Did the fact that it was going to be a film dictate how you approached writing the music?

SB: It did. I wrote all the vocal music first, to a click track, with very sketchy harmonic accompaniment, just as a guide so that the singers had something to go on. Then we recorded them singing to the click track, so we had the audio recording of just their voices. After that, I put in the rest of the score on the computer using virtual instruments and other sounds, which of course didn’t exist at the beginning of the process. It felt almost like when actors have to act to a balloon on a stick because the CGI hasn’t been done, because nobody really knew what what the final score was going to sound like. Including me!

How did you approach shooting the film when it reached that stage?

SB: The film was shot to the vocal recording. We had planned that there wouldn’t need to be any changes, and actually the tempo track would dictate the edit. But in the end there were a couple of places where the visuals needed additional music between vocal passages, which was fine. But we were pretty much completely locked into the singing – obviously it was impossible to change it once it had been recorded.

And how did you find working on the rest of the music after the audio track of the voices had been recorded?

SB: That was quite unnerving, because I knew if I had any doubts about the vocal lines, it was tough. But the fun thing was having the singing in advance and then playing around with different harmonies. I did reharmonise one section. Again, that would never happen in a staged production – to be writing music with a singer’s voice in your ear, rather than just imagining how it would sound. But it was exciting because I could create it exactly as it would eventually sound.

Jenni: why did you make the decision to write the libretto in Scots?

JF: I like writing in Scots, especially poetry, so it made sense to me not just to produce just another standard English opera libretto. I adore the musicality and emotive qualities of language. Scots was the only choice I could have made for this one. It’s important to write in Scots when I want to because the idea that our only ‘proper’ language is English is outdated and doesn’t serve culture at all. There’s a richness and nuance to Scots that I hoped might work brilliantly in a libretto. I also wanted my voices to be far more working-class. It’s a way of challenging expectations of opera. I wanted my characters to be young, dark-humoured, fast-talking, hard-working, flawed people.

And Sam, how did you find setting a libretto written in Leith Scots?

SB: It was quite challenging! It’s hard enough to make English sound good in opera. Doing it in Scots made it even harder. But what was good about the language, as Jenni says, is that it actually removes the work from the world of opera. It takes it somewhere else, away from that tradition. I obviously tried to think about the different pronunciation with the setting. There were some words Jenni used that we just couldn’t make work. Some words just sound ridiculous when they’re sung, whatever the language, so we asked her to change those. But actually you can do different things melodically with Scots and English, so it was very creative in that sense.

How would you describe the themes behind the work?

JF: The themes were narcissism and the undermining and negligence in paying working-class women appropriately for their talent, flair, dedication and hard work.

It’s obviously coincidental that a new film opera should be premiered at the time of a global pandemic, when live performances are suspended. But how would you describe the relationship between The Narcissistic Fish and our current circumstances?

SB: In practical terms, luckily all the work that’s needed to be done on The Narcissistic Fish in post-production has been people sitting individually in studios, which has been great. But we’ve been working on it for several months, and we had no idea it would be coming out in these circumstances. At the back of our minds, we knew it was an experiment in what opera could be, using technology and everything else. And it has suddenly become very relevant.

Two Worlds Colliding

How did The Narcissistic Fish’s three singers adapt to the unique demands of making opera for film, rather than for the stage? David Kettle finds out.

‘The idea of performing in front of a camera (which I’d never done before), and gutting fish, and having to speak and sing in Scots – it was my absolute nightmare. But in the end it was great fun!’ Baritone Mark Nathan has some – well, let’s call them vivid recollections of singing the role of Kai in The Narcissistic Fish. But for a Surrey-born singer with a particular aversion to fish making his screen debut using an accent very much not his own, it was always going to be a memorable experience.

The Narcissistic Fish was memorable, too, for all three of its singers, simply because of the uniqueness of creating it, and how different the process was to that of a staged production, which of course they’re all more familiar with. All three were Scottish Opera Emerging Artists at the time the opera was recorded, near the beginnings of their careers, although still with significant opera experience to their names. But nothing quite like this.

‘It was new for all of us,’ admits soprano Charlie Drummond, who sings Belle. ‘And actually not just for us singers, but also for the Director Antonia Bain and Composer Samuel Bordoli. It was almost as if everyone came together speaking different languages.’

‘Not literally, of course,’ continues Nathan. ‘But there were us and Repetiteur Susannah Wapshott talking musicians’ language, Sam talking composer’s language, and Antonia and the rest of the film crew talking film language. But bringing those three worlds together was really cool.’

Skeleton guidance

But let’s go back to the beginning. And even from the very start, things were somewhat unusual. What the three singers first received is what baritone Arthur Bruce (who sings Angus) describes as ‘a kind of skeleton score. Sam had made a vocal score with some cues and guide notes about what was going to be happening in the music, but because a lot of the accompaniment is electronically produced or manipulated, we didn’t have the finished music to work with.’

Initial musical rehearsals took place with the three singers and Repetiteur Susannah Wapshott, by day Scottish Opera’s Associate Chorus Master and Repetiteur, alongside Director Antonia Bain. ‘We started off getting the vocal lines as right as we could,’ continues Nathan, ‘and Antonia would interject explaining what would be happening dramatically at certain points. So far, it was quite similar to working with a stage director.’

The next stage, however, took the singers – plus Director, Repetiteur and Composer – into the recording studio, in this case the one at Glasgow’s Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. ‘Actually, I think we’d all used that studio before,’ adds Bruce, ‘as we’d all studied at the RCS at some point – Mark and I at the same time, and Charlie a couple of years before us.’

‘We recorded the vocal lines using a click track,’ continues Drummond, ‘and we were wearing headphones, so we could adjust the levels of the click and of the other singers. We recorded all the audio in a single day.’

Even that, the singers felt, was quite a new experience, as Drummond explains. ‘You’re obviously trained to project your voice to fill a hall or an opera house, and then suddenly you’ve got a microphone right in front of you. But it’s liberating, too – you can try riskier things, or things that might be considered risky on stage. There’s much more freedom to try that in a recording environment.’ After all, if something isn’t working, you can simply do it again, and differently.

Mark Nathan, however, points out another fundamental difference between recordings and stage performance: permanence. ‘When you perform on stage, inevitably some things change from performance to performance. But in this case, nothing could change. Once we’d laid down the audio track, that was it, and that was what was going to be heard in the finished film. So it was really hard thinking at that stage: how do I deliver this line? Where am I going to be? Who am I speaking to? What’s my intention?’

Into the film studio

If there were initial challenges, however, they were overcome with input and direction from the broader creative team. And once the audio recording was finalised, rehearsals continued, now focusing on drama, movement and position. ‘We worked with Antonia in one of Scottish Opera’s studios, trying to block what might happen where, and where the camera shots might be coming from – it was obviously difficult as we didn’t have a set at that point. But we were improvising together and working things out between us,’ explains Arthur Bruce.

‘Antonia would tell us: okay, this is what this shot is going to be,’ Nathan continues. ‘Or: this is what we’re going to see at this point. Or even: you don’t need to be in this shot, so you can go into the background and chop some vegetables, and all we’ll see is your shoulder. Or at the other extreme: this is going to be a tight close-up on your face.’

Once the process moved on to the filming itself, another level of unfamiliarity came in. ‘We took the train up to Possilpark in northern Glasgow and walked to an industrial estate. But we were confused because we found a police station where we were supposed to be. So we double checked we had the right place, and eventually found a side door to go in. And we quickly realised this was where we were meant to be. It was a collection of TV and film studios, with a police station set at the front of it. We filmed in a very well-equipped kitchen set: as soon as you put on some chef’s whites, and you’re in a room surrounded by stainless steel equipment, suddenly it all feels much more real.’

Emotional challenges

Perhaps not surprisingly, it was the filming process that felt most different from preparing for a staged production, with its own individual challenges, but also its unexpected opportunities. ‘It was quite refreshing not to have to run the whole thing from beginning to end,’ continues Bruce, ‘and to be able to have multiple goes at different scenes, knowing that any of them might make the final cut.’

Charlie Drummond has different memories. ‘I kind of missed the feeling of a performance of the whole piece,’ she admits. ‘But it made me realise how good film actors are at picking up where they’ve left off, and clicking immediately into where they’ve been.’

Nathan agrees. ‘I remember finding one particular scene quite difficult. I get really furious at Angus and I have to explode at him and lunge at him. Doing that over and over again, and suddenly having to get into that place of anger, and making it feel real every time – it takes a lot out of you emotionally.’

Filming wasn’t without its moments of humour, however. ‘The film crew were amazing,’ says Bruce, ‘and what struck me straight away was that they all had very specific roles, and knew exactly when and how to do what they needed to do. I think some of the guys had never heard opera singing live, though, let alone just two feet away from them – which was maybe a bit of a shock. I’m not the biggest of guys, but I do make quite a lot of noise…’

Singing and miming

Indeed, despite having recorded the audio, the trio of singers weren’t simply miming to it. ‘Convincing miming is incredibly hard to do,’ explains Bruce. ‘Drag artists are extremely good at it, but that’s proper lip-syncing. Even if you’re singing quietly, it’s much easier to make your mouth do what it did at the recording if you do actually sing.’

‘We quickly realised it was pretty obvious if we were just mouthing along,’ agrees Drummond. ‘I think opera singers are trained in such a way that our voices carry so much of our character, so if you’re just miming, it’s very hard to pretend you’re actually conveying a character.’

Even the manner of acting had to be adjusted for the camera. ‘The tiniest expressions on your face register,’ explains Nathan. ‘When you have an audience of 2000 in an opera house, you can’t just convey that you’re sad, for example, by thinking about being sad: you have to show it with your body, your attitude. You can do almost nothing in front of a camera. And it works.’

If there was one particular disappointment encountered during the filming process, however, it came from Drummond, and it was because she wasn’t able to draw on some of her non-musical skills. ‘In a previous life I actually worked in a kitchen, so I was quite excited about going into that environment again,’ she explains. ‘I thought: I can do fast chopping and all that.’ What she hadn’t considered, however, was that professional food stylist Clair Irwin would be taking care of handling the food. ‘Antonia was going to film close-up shots of Clair’s hands and the food, and the wider shots would be me. Except Clair was right-handed, and I’m left-handed. So if she handed me a knife, for example, I’d go to take it with my left hand…’ To avoid any continuity errors, Drummond opted for some wrong-handed knifework. ‘There are a few shots of me cack-handedly chopping things with my right hand – well, it was more of a case of me just hitting the board with the knife, rather than actually chopping anything. I was too nervous to do that!’

Tricky linguistics

One of the surprises of filming for all three singers was the sheer amount of time it all took. ‘We did three days of filming, and they were really long days,’ explains Bruce, ‘and that was for a film that lasts just 13 minutes. But I asked some of the crew whether they’d expect to get more done in a day and they told me that, for a day’s filming, you’d expect only about four to six minutes’ of useable film.’

Ironically, however, one of the project’s biggest challenges had nothing to do with the unusual processes behind The Narcissistic Fish, nor the particular demands of the filming process. It had everything to do, however, with language. Although Nathan is from Surrey and Drummond from Lincoln, both non-Scottish singers had a resident expert in the particular flavour of Leith Scots that The Narcissistic Fish employs. ‘I felt like I’d landed on my feet,’ explains Bruce. ‘It was literally written in the accent I was brought up with – it’s set about 15 minutes from my mum’s house in Leith. My accent’s actually got a lot softer – I lived for four years in Manchester and a couple of years in London – but as a teenager I was very much from Leith. Going to Leith Academy clearly had its advantages after all…’

Dialect Coach Flora Munro was also on hand, and Repetiteur Susannah Wapshott lent a helping ear as well. ‘It meant a lot of hard work with Flora, who was wonderful at coaching us on pronunciation,’ remembers Nathan. ‘And Arthur was really helpful too. But it remained a real challenge for me.’

But how did Bruce feel his two singing colleagues coped with the unfamiliar language? ‘They did a valiant job – they tried really hard, and they were petrified about it. And even for myself, I had to think about singing in my own original accent as well – it was something I’d never done before. Of course, when we sing in English it’s usually in a more standard dialect.’

The Narcissistic Fish is a ground-breaking project in numerous ways, most fundamentally in its melding of opera and film at such a fundamental level. Would its singers do it again? ‘It appealed to a lot of the things that I love about making art,’ says Nathan. ‘And I felt we could be very real and truthful in a way that you should always aspire to on stage too.’

‘It’s been really exciting, and fantastic that Scottish Opera is exploring new things like this,’ agrees Bruce, ‘especially in our current situation, with theatres not available for the time being. We need to find other ways of delivering opera to audiences. There’s no question that opera is still relevant as an art form, of course, but it could maybe use some technological updating. Why shouldn’t there be operas written for YouTube?’

Opera on Screen

From made-for-TV experiments to lavish big-screen productions, opera, television and film have conducted a decades-long love affair – with predictably varied results. David Kettle examines their sometimes tempestuous relationship.

They seem like two different worlds. On the one hand, the visceral immediacy, the flamboyant, grand-scale emotions, the larger-than-life acting, the live, person-to-person experience, the unapologetic, glorious, self-conscious artificiality of opera. On the other, the understated, implicit emotions conveyed in a glance or a raised eyebrow, the pre-recorded objectivity, the close-ups, pans and establishing shots, the studied apparent naturalism of television and film.

Those are gross generalisations, of course. But there’s plenty of truth in them. And yet those two seemingly irreconcilable worlds – however different they might be – have conducted a long-term flirtation since TV and film’s earliest days – a time when, of course, opera was already a far more mature suitor, around four centuries older than its youthful, techno-savvy paramour.

But let’s make a distinction upfront about the fruits of these liaisons. It’s a distinction beween operas conceived and created specifically for the screen – whether that’s a large screen in front of a cinema audience, or a small screen in the corner of a living room – and operas adapted for the screen from existing works originally conceived for the stage.

And though it’s not quite cut and dried, that distinction by and large separates operas on TV from operas on film. There are far fewer (actually, hardly any) operas intended for the cinema that were specifically conceived and created as such. By contrast, there are really quite a few operas that were created specifically for TV, as we’ll find out.

Things began strongly for opera at the movies. Arnold Schoenberg was one of the first composers to get excited about film’s potential, and way back in 1913 planned a silent film to accompany his music drama Die glückliche Hand, though it never came together. Friedrich Feher’s 1936 The Robber Symphony was the first opera specifically conceived as a sound film, but, despite an excited reception from critics who hailed it as the first example of a whole new art form, it was also pretty much the last.

Ironically, one of the most successful original operas conceived specifically for film in our own times comes from another culture entirely. The 2006 movie Opera Jawa by Indonesian director Garin Nugroho is a present-day take on Hindu epic the Ramayana set in a Javanese village, and funnels traditional Javanese music into a form that directly emulates Western opera. The result is breathtakingly spectacular, but undeniably operatic.

This relative absence of operas conceived for the cinema is almost certainly down to issues of cost. Investing the enormous sums required for a feature-length film of a brand new work, let alone securing widespread distribution in a dog-eat-dog commercial marketplace, has clearly proved too much of a challenge. And though TV costs are still considerable, they’re less prohibitively so – and for networks with a public service remit, providing what’s deemed high art to connoisseurs and newcomers alike has evidently been more of a priority. Indeed, as we’ll see, early TV executives felt it was their responsibility to take opera to the broadest possible audience, and to forge new artistic forms in doing so.

The first TV operas

Gian Carlo Menotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors is usually described as the first ‘TV opera’, but strictly speaking, that accolade actually goes to a far obscurer work, the light-hearted Cinderella by jazz bandleader and classical composer Spike Hughes, given its BBC TV broadcast on 13 December 1938. And though not strictly written for television – it had its premiere on BBC radio earlier that year – it’s at least a broadcast opera, if one with a rather short life.

When discussions were underway as to whether it should return to screens the following year, the BBC’s head of television design Peter Bax dismissed it as ‘rather precious and lacking in humour’, and it was politely shelved. That didn’t stop Hughes writing another TV opera, however, and his St Patrick’s Day was premiered the other side of the war, in 1947.

Just four years later, however, TV opera properly made its mark. At its first broadcast on Christmas Eve 1951, it’s estimated that Menotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors was seen by more than five million viewers on 35 NBC-affiliated networks right across America. That’s a staggering figure, almost certainly a larger audience in a single evening than any other opera has drawn across its entire history.

Amahl and the Night Visitors went on to become a seasonal TV institution, in the US at least, with several further TV productions in subsequent years. And with its touching storyline of a wide-eyed disabled boy encountering the Three Wise Men on their way to visit the infant Jesus, its lush, Romantic score and its concise, 45-minute running time, it’s not hard to see why Menotti’s opera was such a success.

Indeed, mass appeal was a big part of Amahl and the Night Visitors’ conception. It was commissioned by NBC, and the brainchild of General Music Manager Samuel Chotzinoff and Artistic Director Peter Herman Adler (who had studied with Anton Zemlinsky in Prague). Adler was one of TV opera’s early pioneers, and would oversee the commissioning of several new operas for NBC over subsequent years, his stated intentions being to ‘bridge the gap between the mass audience and the opera house’ and ‘develop a new kind of opera’.

A strange disregard for television

It’s ironic, then, that Menotti himself later admitted: ‘I must confess that in writing Amahl and the Night Visitors, I hardly thought of television at all.’ That’s despite being asked specifically for a TV opera. Indeed, Amahl and the Night Visitors has had numerous live stagings down the years, and there’s nothing about the work that restricts it specifically to the medium of television.

In an interview from 1981, Menotti went further, showing perhaps surprising scorn for the genre that had brought him such success: ‘I think that opera on television loses as much of a new audience as it attracts. That is because most opera shown on television is so bad. Opera is not for television unless it is written for television. To adapt an opera for television, you need a superb cameraman and a superb director. I frankly believe that most operas are directed abominably, and once you put on television a close-up of a heavily made-up fat singer with her mouth wide open revealing her wobbly tongue and she acts with exaggerated gestures, people just laugh and close the television.’

Harsh, but – perhaps – fair, at least as an observation on stage productions thrown on the screen with little thought as to the fundamental differences between the two genres. It’s a collision that’s become all the more apparent today, of course, with the profusion of live cinema and online streams from opera houses across the world. And, while the aim of those broadcasts is clearly to capture the spirit and atmosphere of a staged performance on screen, today’s singers nonetheless receive special coaching on adjusting their performances with an awareness of the cameras.

But returning to Menotti, there’s an undeniable irony that he should make such a harsh judgement of operas not specifically written for television when Amahl and the Night Visitors feels so much like a stage work, and hardly sets out to exploit of the specific opportunities that TV offers.

He rectified that situation the following decade, however, in a later opera he created for NBC. His 1963 Labyrinth is arguably the first TV opera to rely on effects that could only realistically be created on television (or film) – from a zero-gravity sequence to a train that magically transforms into a swimming pool. Sadly, however, it wasn’t only Labyrinth’s demanding special effects that discouraged further performances. Audiences and critics alike found its allegorical tale of a bride and groom lost in a mysterious hotel rather baffling. Perhaps its subtitle – ‘An Operatic Riddle’ – summed it up all too well.

TV opera spreads internationally

Nevertheless, the remarkable success of Menotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors encouraged NBC to commission a whole series of TV operas in the 1950s and 1960s, including Martinů’s The Marriage (1953) and Lukas Foss’s Griffelkin (1955). The trend spread across the Atlantic to the BBC, which likewise commissioned operas including Arthur Benjamin’s Mañana and Malcolm Arnold’s The Open Window, both in 1956.

It spread to other US television networks, too. CBS set its sights high and commissioned no less a figure than Igor Stravinsky to write The Flood, first broadcast on 14 June 1962. But things didn’t turn out quite as the network hoped. Stravinsky enthused that he appreciated the simplicity, economy and directness that TV offered, indeed required, feeling they were qualities that chimed with his own artistic values. ‘The saving of musical time interests me more than anything visual,’ he said. ‘This new musical economy was the one specific of the medium which guided my conception of The Flood. Because the succession of visualisations can be instantaneous, the composer may dispense with the afflatus of overtures, connecting episodes, curtain music.’

What Stravinsky came up with in The Flood, however, was quite an abstract work melding together opera, dance and spoken text. And though its story – the Biblical tale of Noah’s Ark – was familiar, his treatment was somewhat alienating – not to mention short, running to just 25 minutes. CBS was therefore obliged to pad out its hour-long TV transmission slot with documentary shorts, pious commentary on the Biblical tale and more, all sectioned up by ads, of course. Maybe not surprisingly, critical reaction remained rather cool.

Britten’s Owen Wingrave

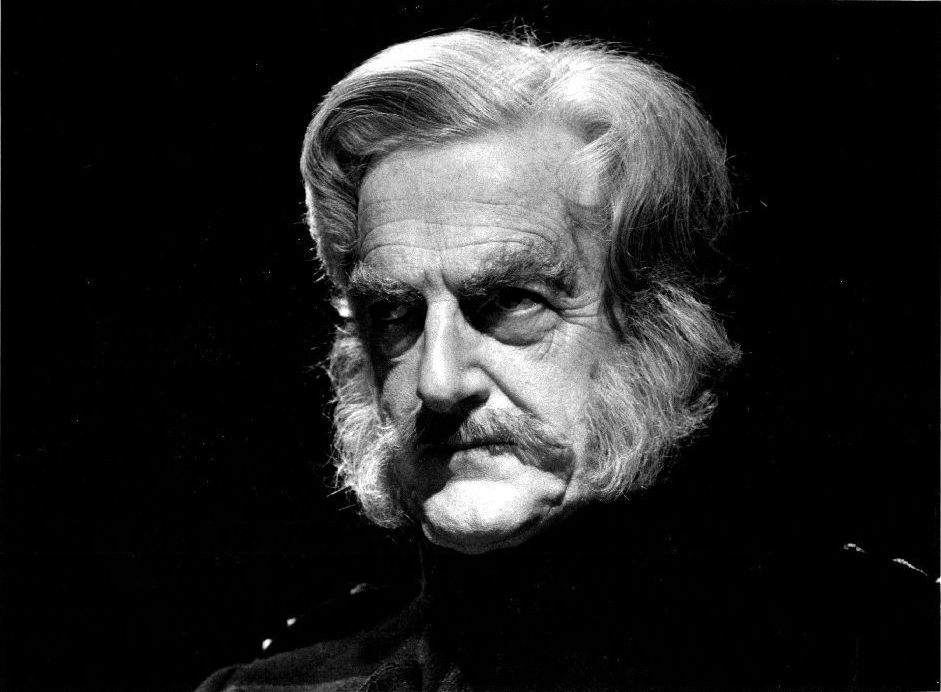

At least ads are not something the BBC has had to deal with. And though it was hardly the network’s first foray into TV opera, in 1966 the BBC embarked on its biggest, highest-profile operatic project, from the country’s most prominent composer. It was none other than David Attenborough, then Controller of BBC2, who commissioned Benjamin Britten to write an opera for television, and who remained closely involved in the project right through to its broadcast on 16 May 1971, travelling to Snape Maltings for Owen Wingrave’s recording the previous November. From the start, Owen Wingrave was planned as a big, ambitious, elaborate work, bringing together a large cast of some of British opera’s most prestigious names, including Benjamin Luxon, Heather Harper, Janet Baker and, naturally, Britten’s partner Peter Pears (pictured below as General Sir Philip Wingrave in the original TV production).

And as with his 1954 The Turn of the Screw, Britten turned to a ghost story by Henry James for inspiration. Owen Wingrave’s eponymous protagonist is the last in the noble line of a proud military family, but his devoutly pacifist beliefs – which mirror the composer’s own – lead him to rebel against his relations’ expectations. Accused of outright cowardice, he is forced to demonstrate his bravery by confronting the ghosts – quite literally – of his ancestry.

And though hardly the most performed of Britten’s operas, Owen Wingrave nonetheless gets its fair share of stage performances, and indeed was conceived for both television and the opera house. In fact, at the time of its 1966 commission, Britten and Pears didn’t even own a television, and it’s been suggested that the composer wasn’t keen on the new-fangled technology. When Snape Maltings was being converted into a concert hall in the mid-1960s, for example, he specifically resisted suggestions that it should incorporate wiring and facilities for TV broadcasts.

Nevertheless, Britten clearly embedded televisual thinking into his conception, right from the opera’s arresting opening, whose series of chiming chords are specifically designed to coincide with changes to camera shots – in this case, showing the portraits of Owen’s forebears, who will play such a decisive role in his eventual fate.

New channel, new vision

More than a decade later, Harrison Birtwistle’s Yan Tan Tethera was another BBC-commissioned TV opera, but one that never received the TV production intended for it. Named after a traditional northern English numbering system for counting sheep in use before the Industrial Revolution (1=yan, 2=tan, 3=tethera, and so on), it’s a ritualistic, darkly magical story of jealousy between two shepherds, imprisoned twin children, and the sinister, devilish Bad’un, set to a libretto by poet Tony Harrison based on a traditional folk tale.

Though it was commissioned jointly by BBC Radio 3 and BBC2 television, the funding had come entirely from Radio 3, and when BBC2 planners got cold feet about a made-for-TV opera production, Radio 3 sought permission from the BBC governors to approach Channel 4 with the project. The commercial network finally broadcast Yan Tan Tethera in 1987 as part of a series of programmes that also featured Birtwistle’s Punch and Judy in a production by David Freeman’s iconoclastic Opera Factory. So delayed had Yan Tan Tethera been, however, that it had already been given its stage premiere, at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall, which is what Channel 4 recorded and broadcast.

Indeed, Channel 4 has had a proud history of opera productions from its launch in 1982, one no doubt inspired by the network’s founding Chief Executive, (Glasgow-born) Jeremy Isaacs, who would go on to head the Royal Opera House as his subsequent job in 1987. It was Isaacs who made a strong commitment to the arts and culture right from the channel’s opening (he warned that he’d throttle his successor, Michael Grade, if he betrayed the trust placed in him about this aspect of the channel’s remit).

Accordingly, in 1989 the channel made the decision to embark on a series of six hour-long, made-for-TV operas. There were very specific stipulations: each opera should be precisely 51:45 in length, including the opening titles and closing credits, to make an hour’s programming when commercial breaks were added; and each should depend entirely on the possibilities offered by TV rather than traditional stage techniques (or, in the words of Channel 4, be ‘unsuitable for live performance’).

The eclectic results, which welcomed in jazz and pop musicians alongside classical composers, were predictably provocative and somewhat mixed, and several have been long forgotten. (The full list, since you’re probably wondering, is: Orlando Gough’s The Empress; Anthony Moore’s Camera; Stewart Copeland’s Horse Opera; Michael Torke’s King of Hearts; Gerald Barry’s The Triumph of Beauty and Deceit; and Kate and Mike Westbrook’s Good Friday 1663.) Of them all, Barry’s Handel-inspired The Triumph of Beauty and Deceit has had the longest afterlife, in several stage productions around the world, including at the 2002 Aldeburgh Festival and its US premiere four years later in Los Angeles.

Despite any notions of success and failure, however, what’s crucial is Channel 4’s commitment to TV opera, and indeed its questioning of what opera can be, in works that strain against any restrictions of form and genre. Some of these works might unavoidably feel dated, but there’s no denying that they were pioneering in their time, nor that they were conceived with the ambition not only to create new operas, but also to redefine what opera even is.

From TV to film

Channel 4 continued its long-standing commitment to TV opera in the 2000s, with Judith Weir’s Crusades-based Armida broadcast on Christmas Day 2005, in a production filmed on location in Morocco, and Jonathan Dove’s Man on the Moon, inspired by astronaut Buzz Aldrin, on Boxing Day 2006. Prior to those two productions, however, came director Penny Woolcock’s ambitious film of John Adams’s controversial The Death of Klinghoffer, shot entirely on location on a specially hired cruise ship in the Mediterranean, and first broadcast on Channel 4 in 2003.

It’s one of the most ambitious – and costly – opera productions to appear on TV screens, and is rightly held up as one of the most successful. The combination of Adams’s operatic treatment of the hijacking of the Achille Lauro in 1985 and Woolcock’s sometimes distressingly naturalistic filming made the production all the more immediate, and therefore all the more comprehensible as an opera experienced via television.

Indeed, so lavish and detailed is The Death of Klinghoffer’s filming that it almost feels as if it belongs in the cinema. As we’ve already seen, however, far fewer operas have been specifically conceived for the silver screen. In fact, if you see an opera at the movies, it’s almost certain to be a sumptuous version of an established classic of the repertoire. There are cases where opera films set out to do little more than entertain and divert, and there’s nothing wrong with that, of course. But when film operas are pioneering, it’s usually in their interrogation or radical reframing of the operas they’re presenting, in the same manner as a probing stage production.

One of the first operas on film was Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s characteristically colourful, vibrant version of Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann from 1951 (pictured above), in which the British film-making partners seemed intent on matching the expressiveness of Offenbach’s music with equally memorable, striking imagery.

Later opera films have achieved some remarkable successes, from Joseph Losey’s politically charged 1979 Don Giovanni (complete with opening epigram by Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci) to Hans-Jurgen Syderberg’s stylised, avant-garde Parsifal in 1982, which overtly interrogates Wagner’s co-opting by the Nazis.

Ingmar Bergman blurred theatre and film in his proto-post-modernist 1975 The Magic Flute, depicting what’s essentially the story of a staging, complete with shots of an appreciative audience, and one in which the singers and the characters they’re playing become increasingly indistinguishable. Watch it on YouTube here

And though not strictly speaking a film of a real opera, it would be churlish not to mention Bugs Bunny’s sole foray into the opera house. Warner Bros’ 1957 cartoon What’s Opera, Doc? is a delectable send-up of Wagnerian extravagance (and, it should be said, of Disney’s Fantasia), with a plot (such as it is) colliding together elements of the Ring, The Flying Dutchman and Tannhäuser as a Siegfried-impersonating Elmer Fudd at first attempts to hunt Bugs, and is then seduced by the Bunny’s unconvincing impersonation of Brünnhilde. Composer Milt Franklyn clearly had lots of fun incorporating Wagnerian leifmotifs into his own typically madcap cartoon score, and it’s interesting to note, too, that back in 1957, it was clearly assumed that cartoon audiences would get at least some of the operatic references. You wonder if the same would be true in 2020. In any case, another of What’s Opera, Doc?’s send-ups is the tragic operatic heroine – which we’ll return to shortly.

And of course, there’s a proud history of directors who have worked equally successfully in both the film studio and in the opera house. Franco Zeffirelli is rightly celebrated in both film and staged opera – perhaps the summation of his work, his sumptuous 1983 movie of La traviata, combines both forms magnificently and regularly tops viewers’ picks of the best opera films. Zeffirelli began his stage career as an assistant to Luchino Visconti, who himself was as celebrated for directing Maria Callas at La Scala as he was for movies such as The Leopard and Death in Venice.

Or just think of Werner Herzog’s many Wagner productions (including Lohengrin at Bayreuth in 1987), or Terry Gilliam’s The Damnation of Faust and Benvenuto Cellini for English National Opera. There are more surprising examples, too. How about Woody Allen, who grappled with Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi in Spoleto and Los Angeles in 2015? Or revered Austrian director Michael Haneke, who brought his unforgiving, clinical analysis to a chilly, straight-faced Così fan tutte in Madrid in 2012?

From movie screen to opera house

But rather than operas transformed into movies, many of the most fruitful collisions between the two art forms, in recent years at least, have occurred in the opposite direction: movies transformed into operas.

Particularly close to Scottish Opera’s heart is Missy Mazzoli’s 2016 Breaking the Waves, given its European premiere by the Company at last year’s Edinburgh International Festival, and based on the controversial 1996 film by Lars von Trier in which a woman attempts to heal her paralysed husband through her own increasingly extreme sexual liaisons with other men.

Another of the iconoclastic Danish director’s films got the operatic treatment, too: his 2000 movie Dancer in the Dark, already a musical (and starring Björk as the poverty-stricken, near-blind immigrant Selma fighting to save the eyesight of her son), became a fully fledged opera in 2007 in the hands of von Trier’s compatriot Poul Ruders. Tragic heroines prove a rather problematic bridge between these two worlds: von Trier has been criticised for subjecting his female lead characters to unremitting misery and often cruel demises, so it’s perhaps hardly surprising that the world of opera, populated as it is by abused and unhappy women, has found his work such a comfortable fit.

Elsewhere, British composer Thomas Adès unveiled his operatic version of Luis Buñuel’s claustrophobic 1962 film The Exterminating Angel at the 2016 Salzburg Festival to great acclaim, and Nico Muhly’s Hitchcock-inspired Marnie was premiered at English National Opera the following year. More radically, Austrian composer Olga Neuwirth made an operatic version of David Lynch’s notoriously bewildering Lost Highway in 2003, in which a jazz musician, framed for the murder of his wife, inexplicably tranforms into an entirely different man while in prison. Neuwirth’s eclectic creation, blending spoken dialogue with sung text (its libretto is by Nobel prize-winner Elfriede Jelinek), and acoustic instruments with brooding electronic soundscapes, is just as elusive and idiosyncratic as Lynch’s dreamlike movie.

Horror opera

Most unusual of all, however, is the 2008 opera by Howard Shore (best known for his soundtracks to the Lord of the Rings movie trilogy) based on David Cronenberg’s 1986 horror movie The Fly, premiered to rather cool reviews in Paris in 2008. It was Shore who wrote the music for Cronenberg’s original movie, and likewise Cronenberg who directed Shore’s opera on the stage. Horror opera is a genre that’s seldom been explored, and judging by the reception that Shore’s The Fly received, there’s perhaps a reason for that.

And part of that reason, perhaps, is that horror is a genre most strongly associated with film, one that exploits the special effects, the jump-scares, the brooding menace that film can so readily generate, and which opera struggles to evoke. And as such, The Fly demonstrates why meldings and meshings between the two worlds don’t always produce results that are greater than the sum of their parts.

No, it doesn’t always work. And there’s no denying that relations between opera, film and television have been messy, chaotic, sometimes hit and miss. But they’ve also often been brilliantly creative. Some remarkable works have been produced in the intersection of film/TV and opera, in pioneering cross-fertilisations that have succeeded in both directions.

And though elements of their respective styles and vocabularies might make film/TV and opera seem like two irreconcilably different worlds, there’s a crucial factor that unites them: suspension of disbelief. Whether it’s accepting the larger-than-life stories and over-the-top flamboyance of grand opera, or the more implicit, calculated artificiality of film, they both demand that viewers surrender themselves to their all-consuming, sometimes overwhelming experiences. Not for nothing do both happen (usually) in darkened rooms, designed to eliminate distractions and make the experience as immersive as it can be. Opera and the screen (whether large or small) have conducted a chequered relationship of liaisons and rejections, generating offspring both celebrated and unwanted, but it’s a noble lineage to which Scottish Opera’s The Narcissistic Fish adds its own distinctive contribution.

David Kettle is Scottish Opera’s Programme Editor. He is also a music critic for The Scotsman and The Daily Telegraph, and has written about music for a broad range of publications including Classical Music, The Strad, The List, The Times and BBC Music Magazine.

A Dangerous Tongue

Once sneered at and actively suppressed in education and officialdom, the Scots language has reasserted its right to be heard and its cultural importance in recent decades. Alistair Heather celebrates its rich history across literature and opera – writing in both English and Scots.

The Narcissistic Fish is exciting. It’s exciting in itself as a piece of work, but it’s also exciting because of its medium. It’s mostly in Scots, my native tongue, and the language of one-third of Scotland’s population. It’s a tongue that has been denigrated, sidelined, beaten out of children’s mouths in school, and shamed in wider popular culture. But it is one that is now benefiting from a modern cultural renaissance. Its re-emergence in opera is a further sign of its social rehabilitation as one of our recognised national tongues. The opera’s reception will indicate how far that rehabilitation has come.

I say re-emergence, because Scots and opera go way back. But we’ll get to that.

Scots is one of Scotland’s three indigenous spoken languages, alongside Gaelic and English. It is Germanic, brought to Scotland by farmer-settlers from what’s now Denmark and Germany. Full of borrowings, Scots can sound like a babble of English, Dutch, Danish and Gaelic as if some radio, set bobbing upon the waves of the North Sea, collected and amalgamated all the signals it could catch. German speakers will recognise the Scots ‘tae ken’ (kennen, to know), Danish folk ‘clatty’ (dirty, like klatte, to daub or smear) and French speakers will see their expression se fâcher (to get angry) reflected in the Scots ‘tae fash’.

Bloodthirsty romps and powerful poetry

The emergence of Scots as a distinct language from its shared roots with Old English began during the founding of Scotland as a medieval kingdom. The first two serious Scots works that survive are poetic trumpet blasts of patriotic Scottishness. The first was written in Aberdeen in the 1300s. It’s a lively account of the life of King Robert the Bruce, and was followed in the 1400s by the poetic story of William Wallace in Scots verse, a bloodthirsty ahistorical romp that captivated centuries of Scots and helped cement the Wallace myth as part of our consciousness. It was the inspiration behind the 1995 film Braveheart, incidentally.

As Scotland settled into its role as an active small European kingdom through the late Middle Ages, Scots experienced something of a golden age. Court poets, called Makars, produced profound works, extending the limits of the language that had become the tongue of the majority across the Lowlands. Virgil’s Aeneid was translated into Scots in 1513 by Gavin Douglas, its first translation into any Germanic language. The archives of the National Library groan yet under the weight of medical publications, government decisions, court records, verses and letters written in various registers of Scots in this period.

It was not to last. The Union of Crowns in 1604 and later Union of Parliaments between Scotland and England in 1707 removed Scots’ status as a courtly and regal tongue, and it was steadily supplanted by English in elite circles. A counter-cultural movement exploded to oppose this Anglifying trend. What’s generally considered Scotland’s first opera was one of its earliest results.

A political opera

This ballad opera was a 1730s conversion of the hugely popular play The Gentle Shepherd by Jacobite and anti-Union writer Allan Ramsay. It opens with these lines:

Beneath the sooth side o a craigy bield,

Where crystal springs their halesome waters yield,

Twa youthfu shepherds on the gowans lay,

Tentin their flocks ae bonny morn o Mey.

The opera was deeply political. Jacobite undercurrents pulled beneath its pastoral surface. Its use of Scots was similarly charged. Ramsay was reclaiming a separate Scottish cultural sphere that had been imperilled by the Union. Activity like this helped keep the Jacobite pot boiling between the great risings of 1715 and 1745, and aimed to restore Scots as a literary language fit for high culture.

Ramsay’s high-energy pushing of Scots as a literary medium forked much lightening in his day. He kept up correspondence with many writers across the country, encouraging their efforts, and published popular collections of the latest Scots works. Many writers followed directly on from him. Among them are some of the brightest lights in the Scottish literary firmament: Robert Fergusson of Edinburgh, and later in the century big Rabbie Burns of Ayrshire. All three poets saw themselves continuing a Scots verse tradition established by the Makars in the 15th century, one they felt it their patriotic duty to continue.

An unrelenting campaign

Their tradition was one of rebellion. It was tied to the Jacobite threat, and fired by opposition to the eliding of Scottish culture within the new British state. Critic Paul J Korshin has gone as far to claim that 18th-century Scottish literature was ‘the product of a Jacobite century’.

Indeed, Scots was slowly squeezed out of official spheres. In 1872 an education act was passed declaring English to be the language of the classroom. This further pressured Scots, as well as giving already suppressed Gaelic another kick. Attitudes hardened still further in the following century. A 1940s Advisory Council on Education report advised schools that ‘against such unlovely forms of speech masquerading as Scots we… should wage a planned and unrelenting campaign’. The language seldom featured on the radio and television broadcasts through the century, and it retreated ever further out of print and popular usage.

In Jacobite times, Scots was dangerous. In the 20th century, it became so again. In the shadow of World War I, Hugh MacDiarmid, a poet committed to Scottish independence, re-fired the Scots poetic world with its rebellious spirit and began a new Scots literary renaissance. The William Wallace story was dusted down and sent out onto the stages of the 1960 Edinburgh International Festival in an all-Scots production. The tongue was in the centre of the cultural fray once more.

MacDiarmid called this movement ‘a propaganda of ideas’, and his efforts underpin much Scottish cultural life today.

In the 1990s James Kelman created How Late It Was, How Late, a Scots novel strong enough to win the Booker Prize, and rebellious enough that one of the judges resigned in protest against it winning. Irvine Welsh’s famous Trainspotting drew heavily upon Scots, and upon profanity, to widespread shock. In the late 1990s, work ‘in Scots [was] still a political step’, ‘clearly a statement of national and cultural politics’, according to German academic Katya Lenz.

Renewed confidence

The Scots literary scene was part of rising tide of cultural assertiveness. Scottish history, Scottish literature, even Scottish folk music experienced fresh impetus, fresh study and a vastly increased audiences. Cultural shift was reflected in politics in 1997, when Scotland’s Parliament reconvened in Edinburgh after nearly 300 years.

Scots has benefited significantly from this change in Scottish self-perception. Far from the 1940s desire to wage an ‘unrelenting’ campaign against Scots in classrooms, the Scottish Qualifications Authority now provides materials to teach it. The Open University recently launched a free online course on the language, and it forms a still small but increasing part of our media landscape.

But if the cultural role that Kelman and others’ work played was similar to that of Ramsay’s, Scots itself had changed. No longer was Scots the homogeneous language of a nation. It had become the dialectical voice of distinct regions and of individual speakers. Kelman’s Scots is unmistakably Glasgow. Welsh unequivocally uses the port-patter of working-class Leith. Scots has a number of very distinct regional dialects, all with their own strong literary traditions. Thanks to the ground broken by writers late in the last century, we are becoming increasingly accustomed to seeing and hearing our local selves reflected in our ‘national’ art.

The Narcissistic Fish is emerging into a Scotland that is increasingly ready for it. Yet it seems ready to drive the conversation on further. In recent years we’ve seen Handel’s Messiah translated and performed in the Scots dialects of the north-east and also of Ulster. Hirda, an original opera by Chris Stout and Gareth Williams in Shetland Scots, was premiered in 2016, and the Scots Opera Project has performed several works in translation. The Narcissistic Fish takes this further, by placing Scots at the heart of an important new work by Scotland’s national opera company. Its libretto, written in conversational, at times profane Leith Scots, clearly follows on from Kelman, Welsh and others.

Producing this opera in Scots shows that The Narcissistic Fish is operating at a sharp creative edge. It throws itself boldly into current cultural discussions. It’s an exciting moment. Its production tells us creatively where Scotland is looking. Its reception will tell us more about where Scotland is.

***

‘Lots ay braw lassies whae’ll catch yer eye…’

‘Any my type? You ken, dinnae answer back so much…’

These lines fae The Narcissistic Fish arnae whit ye’d cry the densest o Scots. It’s a hunner mile awa fae the ‘synthetic Scots’ o MacDiarmid’s verses, an shaws nane o Ramsay’s habit o recuperatin aulder vocab intae his warks tae Scots them up a bit either.

I wadnae expeck ony English monoglot that’s bade in Scotland for mair than five meenitues tae hae trouble unfanklin the meanin o the script. Maist fowk watchin it micht no immediately recognise whit they’re seein as bein pairtly in a leid that isnae English. They’ll mibbie jist identify it as ‘they are speakin like I dae’.

Sae, gin the Scots o The Narcissistic Fish is maistly a mixter maxter o common Scottish English an spoken Scots, how come it’s somethin tae craw aboot at aa?

Weel, it maitters cause Scots is at risk o deein oot. Ane o the main reasons that the Scots o The Narcissistic Fish is a bitty wersh compared wi that o Ramsay’s The Gentle Shepherd is that the vocabulary o Scots in common usage has been dwinin awa. Scots, alang wi sax thoosan ither leids aroon the warld, is mairkit doon as ‘vulnerable’ by UNESCO. Tae rax oot tae a modren Scottish audience, the opera maun yaise modren Scots.

Scots has lang suffered fae a lack o status. It’s been the leid o the fairm, o the mine, o the shipyairds an o the streets. But it hasnae been yaised in high politics, airt, science. It’s suffered fae the ‘Scottish cringe’, the Caledonian affliction that gars Scots shudder whan they hear somebody speakin ‘common’ ootside the correct sphere.

They deys o official suppression o Scots are by. But the language polis bide on, inheritin the ‘cringe’ fae their parents wha were gied the belt fir yaisin Scots. We’ve spake aboot the stramash that eruptit whan Kelman was awardit the Booker Prize. Whan Scots cam back intae opera in 2013, it wis gied a similar treatment.

Scottish Opera pit on a wee stagin o an opera fir bairns in Glasgae Scots, Platypus in Boots. It wis weel received, but the language wisnae. The writer o the piece telt me that ae reviewer blogged that there was ‘no place for the Glaswegian Scots language in the opera style’. Even the guid auld Glasgae Herald claimed that there’s an ‘odd opposition between the Glesca’ patois and the operatic register’. Opera wis owre fantoosh tae be mixin wi yer gutter tongue. The writer o thon opera wis pit aff, an telt me the experience wis ‘the end of [their] Glaswegian opera foray’.

Sae recently as 2019, oor Scots screiver (and ae-time opera owresetter) Michael Dempster described oor ashamed cultural attitude tae Scots as ‘a fracture in our society that needs to be healed’.

Gin we dinnae heal the fracture, Scots voices will aye be marginalised, Scots itsel will cairry on dwinin awa, an oor airts will tyne ae wey tae communicate wi their audience.

Sae tae see Scottish Opera comin back wi mair Scots wark is important. Mibbie, as the Scots renaissance ongoin the noo gaithers momentum, an Scots re-enters aa levels o life, thon fracture in oor society that maks it weird fir us tae hear ourselves on stage will at lang last be healed.

(Haein a bit o a tyauve wi the text? Check oot the Scots dictionary at dsl.ac.uk. / Needing help with some of the text? Have a look at the online Scots dictionary dsl.ac.uk)

Alistair Heather is a Scots columnist and writer. He recently wrote and presented a BBC documentary on the Scots language, Rebel Tongue, streaming now on the BBC iPlayer.

Biographies

Antonia Bain – Director

Scottish Opera’s in-house film-maker Antonia Bain studied fine art at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design. An internship with multimedia design company 55degrees led to a full-time role as content producer, and in that role she made several short films for Glasgow’s award-winning Riverside Museum. She has made short films, music videos and short documentaries. She joined Scottish Opera in 2015 and has produced promotional and cultural films for the Company’s social media and website. Highlights include creating a filmed performance of former Scottish Opera Composer in Residence Lliam Paterson’s piece In Glasgow, based on Edwin Morgan’s poem, and an opera/pop crossover with Scottish singers Be Charlotte and Carla J Easton as part of the BBC’s #OperaPassion Day. The Narcissistic Fish is her first opera short film for Scottish Opera.

Samuel Bordoli – Composer

Samuel Bordoli ARAM is Scottish Opera’s Composer in Residence. During the 2017/18 Season he composed Wings and three piano interludes for the Opera Highlights tour, and Grace Notes to complement the Company’s production of Ariadne auf Naxos. In the 2018/19 Season, he composed an Overture and To Music for the Autumn 2018 Opera Highlights tour, as well as Le trésor des humbles for soprano and orchestra, premiered in March at Aberdeen’s Music Hall. He studied at Birmingham Conservatoire and London’s Royal Academy of Music, where he was the Mendelssohn Scholar. He was mentored by Peter Maxwell Davies for nine years. His broad output has included a chamber opera, Amerika, performed at the Tête à Tête opera festival in London, and a choral anthem, The Great Silence, premiered at the Windsor Festival for the Queen’s 90th Birthday. His music theatre piece Belongings was premiered on the Caledonian Sleeper between Aberdeen and London. He has also composed four Live Music Sculptures, site-specific compositions for London landmarks, including Tower Bridge, the Monument and St Paul’s Cathedral, and co-produced Planets 2018, a new ‘Planets Suite’ performed inside planetariums across the UK.

Arthur Bruce – Angus

Scottish baritone Arthur Bruce is The Robertson Trust Scottish Opera Emerging Artist 2019/20. He is a graduate of the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland’s Opera School, the Royal Northern College of Music, English National Opera’s Opera Works programme and Scottish Opera’s Connect Ensemble. He is a Britten-Pears Young Artist.

Scottish Opera appearances: Amadeus & The Bard, Opera Highlights Spring 2020.

Operatic engagements include: title role Gianni Schicchi (RCS Opera School); Papageno The Magic Flute (Berlin Opera Academy); Zurga The Pearl Fishers (Edinburgh Grand Opera); Guglielmo Così fan tutte (London Young Sinfonia); Wolfram Tannhäuser (Edinburgh Players Opera Group); Sam Trouble in Tahiti (RCS Opera School); Prince Yamadori Madama Butterfly (Bowdon Festival Opera).

Charlie Drummond – Belle

Born in Lincoln, Charlie Drummond is a Scottish Opera Emerging Artist 2019/20. She studied at King’s College London, the Opera School at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland and the National Opera Studio. She is also a Samling Young Artist.

Scottish Opera appearances: Opera Highlights Autumn 2019, Iris.

Operatic engagements include: title role Anna Bolena (cover) (Longborough Festival Opera); Donna Anna Don Giovanni (British Youth Opera); Rosalinde Die Fledermaus, Fiordiligi Così fan tutte, Countess The Marriage of Figaro, Mrs Julian Owen Wingrave, Eleonora Prima la musica e poi le parole by Salieri (RCS); Sofia Il signor Bruschino (Raucous Rossini); Serena Farage The Secretary Turned CEO by Danyal Dhondy – world premiere (Lucid Arts); Voice Simoon by Erik Chisholm – world premiere (Music Co-OPERAtive Scotland).

Jenni Fagan – Librettist

Born in Scotland, poet and novelist Jenni Fagan graduated from Greenwich University and won a scholarship to the Royal Holloway MFA programme. She is currently completing a PhD on structuralism and Kafka’s Metamorphosis at the University of Edinburgh. She has won awards from organisations including Creative Scotland, Dewar Arts and Scottish Screen, and has twice been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. She was selected as one of Granta’s Best Young British Novelists after the publication of her debut novel, The Panopticon, which was shortlisted for the Desmond Elliott Prize and the James Tait Black Prize. Her own adaptation of The Panopticon was staged by the National Theatre of Scotland. Her second novel, The Sunlight Pilgrims, was shortlisted for the Royal Society of Literature Encore Award and the Saltire Fiction Book of the Year Award, and won her Scottish Author of the Year at the Herald Culture Awards. Her third novel, Luckenbooth, is due for publication in January 2021. She has also published four collections of poetry, and recently directed her debut short film. She has written a second short film, Isolation, as part of the National Theatre of Scotland’s Scenes for Survival project, which is being shown on BBC iPlayer and online. The Narcissistic Fish is her first opera libretto.

Mark Nathan – Kai

Born in Surrey, Mark Nathan is a Scottish Opera Emerging Artist 2019/20. He is a graduate of the Opera School at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, where he studied with Scott Johnson, following earlier studies at Birmingham University and London’s Royal College of Music.

Scottish Opera appearances: Rabotnik The Fiery Angel, Opera Highlights Autumn 2019.

Operatic engagements include: title role Don Giovanni, Marcello La bohème (Opera Loki); Papageno The Magic Flute (Hampstead Garden Opera); Joseph De Rocher Dead Man Walking, Death Savitri, Director Les mamelles de Tirésias (RCS); Joseph De Rocher (cover) (Welsh National Opera, Israeli Opera); Dr Falke Die Fledermaus, Judge and Counsel Trial by Jury, Wagner Faust (Winterbourne Opera); Jack Point The Yeomen of the Guard (Portsmouth Guildhall); Koko The Mikado (Co-Opera); Dr Pangloss Candide (London Musical Theatre Orchestra); Sir Joseph Porter HMS Pinafore (Harwich Festival of the Arts); Doctor La traviata (Opera Euphonia); Gob The Poisoned Kiss (Barber Institute Summer Festival); Moralès Carmen (Riverside Opera).

Production Team

Director of Photography

Gordon Ballantyne

First Assistant Director

Stuart Cadenhead

Dubbing Mixer

John Cobban

Colourist

Colin Brown

Editor

Lucy Armitage

Executive Producer

Andrew Lockyer

First Assistant Camera

Andy Brown

Second Assistant Camera / DIT

Tom Armstrong

Additional Footage

David McGinty

Audio Engineer

Bob Whitney

Sound Assistant

Benny Robb

Lighting Gaffer

Derrick Ritchie

Console Operator

Joe Breslin

Food Stylist

Clair Irwin

Hair and Make-up

Ana Cruzalegui

Carol Fairfield

Repetiteur

Susannah Wapshott

Dialect Coach

Flora Munro

Production Managers

Catriona Downie

Emily Henderson

Props Supervisor

Marian Colquhoun

Props Assistant

Jenni Murison

Deputy Head of Costume

Lorna Price

Costume Supervisor

Jasmine Clark

Scottish Opera Elizabeth Salvesen Costume Trainee

Workshop Manager

Edd Smith

Set Builders

Andrew Steel

David Gillies

Aaron Goddard

Audio Description

Jonathan Penny

Support us

Enjoy what you've seen? Please help us create the next Scottish Opera Short by donating online today.

Looking for the film?

You can watch the full film on our website from Thursday 18 June at 7pm.