Spotlight on...

The Gondoliers

Sunny, funny and with more ‘tra la las’ per square inch than any other opera in the canon, The Gondoliers is a joy from start to finish.

In a flight of the satirical whimsy so typical of G&S, two happy-go-lucky gondoliers discover that one of them is, in fact, heir to the throne of a distant kingdom. True to their (adopted) Republican roots, they set off together to rule in idealistic, if somewhat chaotic, style...

Originally planned for stages across the country from May to July 2020 in a co-production with D'Oyly Carte Opera & State Opera South Australia, The Gondoliers will return in a fast, furious production by Stuart Maunder, Artistic Director at State Opera South Australia, as soon as restrictions allow.

In the meantime, take a delicious bite of Gilbert and Sullivan’s glorious confection in a specially recorded video of highlights and commentary, featuring four of the singers due to perform in the new production – Sioned Gwen Davies, Ellie Laugharne, Ben McAteer and William Morgan – alongside the production’s Conductor, Scottish Opera Head of Music Derek Clark.

A special thank you to all those supporters who donated to our Play A Supporting Role appeal, helping to create this wonderful production. We can’t wait to show you how the work has turned out.

Spotlight on... The Gondoliers (Act 1)

Spotlight on... The Gondoliers (Act 2)

Director’s Introduction

Stuart Maunder, Director of the production of The Gondoliers originally planned for May to July 2020, looks forward to bringing the joyful work to stages in the future

Who’d have thought it was just a few months ago when I was lunching with Scottish Opera General Director Alex Reedijk at a popular Adelaide restaurant, when the Company’s extraordinary production of Breaking the Waves was about to wow audiences at the Adelaide Festival? Rehearsals for The Gondoliers were only three weeks away; schedules had been posted; Dick Bird, our designer, had been sending snaps of early costume fittings; and WhatsApp was alive with discussions with choreographer Anjali Mehra-Hughes. Phrases such as ‘self isolation’, ‘social distancing’ and ‘Zoom meeting’ had yet to find regular places in our daily discourse.

We all know what happened the following weekend.

So it’s a waiting game, and none of us can possibly know when the situation will end. One thing is clear, however. When we come out of the current state – and we will come out of it – we’re ready to go. The Gondoliers will be there, ready to delight.

We know the post-Covid operatic landscape will look very different, but at base our artform will continue to thrive. It’s thrived through worse than this – war, revolution, social upheaval. Opera relies on bringing people together in one place, at one time, to have a shared experience of the great works. That remains our goal.

And we’ll achieve that goal just as soon as it is safe to do so. We will be there, ready, willing and champing at the bit to deliver this great piece. We will see you at The Gondoliers!

Conductor's Introduction

Scottish Opera’s Head of Music Derek Clark reveals his abiding love for Gilbert and Sullivan

The Gondoliers was the first Gilbert and Sullivan operetta I got to know well. My parents took me to a D’Oyly Carte performance when I was about ten, and shortly afterwards my dad acquired a second-hand vocal score from which I tried to play the various songs. (I still have it, and though it’s now quite fragile, I was able to use it for some of the recordings for this project.)

So began a love of the works of Gilbert and Sullivan that continued as I gradually discovered all the operettas, sometimes by seeing them (mainly in amateur productions by the Glasgow Orpheus Club, one of whose members worked in my dad’s office and always got us tickets) and sometimes by acquiring scores as birthday or Christmas presents, and getting to know the music for myself by playing it – always a better way of learning!

Stuart Maunder, our director for The Gondoliers, mentions below discovering Martyn Green’s Treasury of Gilbert and Sullivan as a teenager as a seminal moment in his relationship with these pieces. I too discovered a copy of that book in my local library, at around the same age, and it probably spent more time on my piano than it did on the library shelves! It formed a wonderful introduction, particularly to the music of some of the lesser-known pieces, and the opportunity to see Gilbert’s lyrics and dialogue on the written page helped me to appreciate the cleverness of his wit and his verbal dexterity.

As a student, I was able to take part in a couple of productions by the Glasgow University Cecilian Society, singing in the chorus (my score of Iolanthe still has copious pencilled instructions about what we were supposed to do on stage). Later, as a repetiteur at Welsh National Opera, I was privileged to help with the musical preparation of recordings of some of the pieces made by Charles Mackerras, whose knowledge of this repertoire was second to none. (I also got to play the celeste in a performance he conducted of his wonderful arrangement of Sullivan’s music for the ballet Pineapple Poll. There wasn’t much to play, but hearing his orchestration ‘from the inside’ was great fun, and seeing his obvious delight in the music made an indelible impression.)

During my time at Scottish Opera, it has been a ‘source of innocent merriment’ to include some Gilbert and Sullivan extracts in our Opera Highlights touring programmes – quite often from the lesser-known pieces – and to see how well they go down with the audiences. And of course more recently it’s been a great joy to have conducted performances of The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado, as well as preparing the chorus for the Edinburgh International Festival performance of HMS Pinafore.

It’s widely held that The Yeomen of the Guard is the most obviously ‘operatic’ piece in the G&S canon, and therefore the one most likely to appeal to those who spend their lives working in opera houses. But while Yeomen contains much wonderful music, the piece I’ve always maintained is most suited to be given the full ‘operatic’ treatment is The Gondoliers. So I was particularly delighted not only when Scottish Opera decided to plan a production, but also when I was asked to conduct it, since it was something that I had always wanted to do. The chance to collaborate with another G&S enthusiast, director Stuart Maunder, would be a lot of fun, and, having seen the designs for sets and costumes created by Dick Bird, I quickly realised that our audiences would enjoy a visual treat as well as (hopefully) a musical one.

We very much hope that we’ll be able to welcome you to a live performance of The Gondoliers soon. For now, though, we can at least present some of the music, together with a little background context. I’m very grateful to the four singers – Ellie Laugharne, Sioned Gwen Davies, William Morgan and Ben McAteer – who not only readily agreed to record, in the middle of lockdown, portions of the roles they were to sing in our production, but also happily learned extracts from other roles so we could give you a fuller picture of the musical landscape of this lively operetta. Enjoy!

Biography: Gilbert and Sullivan

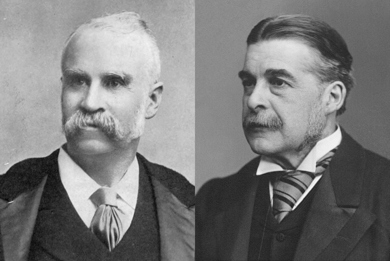

Sir William Schwenk Gilbert Born: London, 1836. Died: Harrow Weald, 1911

Sir Arthur Sullivan Born: London, 1842. Died: London, 1900

WS Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan first worked together in 1871 on the light opera Thespis, which was not a success. It was in 1875 that the entrepreneur Richard D’Oyly Carte brought them back together for the hugely popular Trial by Jury. From then on, one runaway success followed another. HMS Pinafore was an international sensation in 1878, as were The Pirates of Penzance in 1879 and Patience in 1881.

The two men were very different, however. Sullivan’s father was a military bandmaster, but the young Arthur quickly outstripped him, composing his first anthem at the age of just eight. After a spell as a Chapel Royal chorister, the 14-year-old received a scholarship to study at London’s Royal Academy of Music and later the Leipzig Conservatoire.

Gilbert came from a wealthier background and trained as a barrister. His parents feuded all through his childhood and continued to bicker even after they separated. While Sullivan was effortlessly charming, Gilbert had a reputation for irascibility.

Aside from his operettas, Sullivan also composed ballets, incidental music, symphonies and concertos. He was proclaimed as Britain’s first home-grown musical genius since Purcell, and grew discontented that his comic operettas were better known than his more serious work.

Sullivan received a knighthood in 1883, but, following a disappointing reception for Princess Ida the following year, he rejected Gilbert’s next libretto ideas. Fortunately the opening of London’s Japanese Village in 1885 inspired Gilbert to write The Mikado, their most successful opera and the work that rescued their partnership. Their last successful collaboration was The Gondoliers in 1890, but during its run at the Savoy, Gilbert fell out with Carte and Sullivan over carpeting and other incidental costs at the theatre and broke up the partnership.

Four years later, Gilbert and Sullivan, reunited for two last operas, Utopia Limited and The Grand Duke, but they achieved less success. Sullivan, never in good health, predeceased Gilbert by 11 years. Gilbert died of a heart attack while rescuing a young woman from drowning.

Adrian Mourby

Synopsis

Act I

In Venice, 24 farm girls declare their passions for the handsome gondolier brothers Marco and Giuseppe Palmieri, who blindfold themselves in order to choose their brides fairly. Eventually, Giuseppe picks Tessa, and Marco picks Gianetta, and all four head to church for a double wedding.

The Duke and Duchess of Plaza Toro, along with their daughter Casilda, arrive from Spain to meet with Don Alhambra del Bolero, the Grand Inquisitor. While their drummer Luiz departs to announce the Duke’s arrival, the Duke and Duchess reveal to their daughter a secret they have kept for 20 years: when she was just six months old, she was married to the infant son of the King of Barataria, who was spirited away to Venice by the Grand Inquisitor, and is now King himself following his father’s demise in an insurrection. Casilda is therefore now Queen of Barataria, and her parents have brought her to Venice so that she can meet her husband. Secretly in love with Luiz, Casilda resigns herself to a life apart from him.

The Grand Inquisitor arrives, and explains that the baby Prince of Barataria was raised by the Venetian gondolier Baptisto Palmieri, who had a son of a similar age and quickly forgot which was which. The two boys – Marco and Giuseppe Palmieri – grew up to become gondoliers themselves. Only the nurse Inez who looked after them (and who also happens to be Luiz’s mother) knows which is which, but she is now living with a brigand in the mountains. The Grand Inquisitor sends Luiz to find her.

When Marco and Giuseppe arrive with their wives, Don Alhambra explains that one of them is the King of Barataria, but nobody knows which one. Despite their Republican beliefs, the ‘brothers’ are delighted, and agree to travel to Barataria at once, acting together until the real King can be identified. Don Alhambra advises their wives that they cannot be admitted to Barataria until the King has been declared – neglecting to mention that the real King is already married to Casilda.

Act II

In Barataria, Marco and Giuseppe are enjoying splendid lives, but nonetheless miss their wives. Themselves struggling to endure the separation, the ladies soon arrive from Venice, and all celebrate with a grand ball.

Don Alhambra arrives at the palace to discover that Marco and Guiseppe have promoted everyone to the nobility, and breaks the news that the true King was married to Casilda as a baby – and is therefore an inadvertent bigamist. The gondoliers’ wives are distraught to discover that neither of them will be Queen.

The Duke and Duchess of Plaza Toro arrive with Casilda, and, shocked by the lack of pomp and ceremony to welcome them, set about educating Marco and Giuseppe in proper royal behaviour. The two erstwhile gondoliers are left alone with Casilda, who promises to be a loyal wife to one of them, and when their other wives arrive, all five sing of their strange predicament.

Don Alhambra arrives with the nurse Inez who knows the King’s true identity. She confesses that when the Grand Inquisitor arrived to steal the baby Prince away, she substituted her own young son, keeping the true Prince under her own guard. Thus it is neither Marco nor Giuseppe who is King, but Luiz – and Casilda discovers that she is already married to the man she loves. The two gondoliers, though disappointed not to be King, return to Venice happily with their wives.

The Perennial Charms of G&S

What gives Gilbert and Sullivan their longevity? Stuart Maunder ponders their gleeful satirical inventions

There’s no theatrical phenomenon in the English-speaking world with the staying power of Gilbert and Sullivan. The G&S phenomenon has been part of our basic language of performing for more than a century. People sing the numbers in competitions; musical societies stage the pieces all the time; and not so long ago families sang the songs around the piano or pumped ‘selections’ from them at the pianola. The idea that a successful performance of ‘something from G&S’ is within reach for those who want to achieve it is very powerful in our psyche.

Memory plays a big part in our love affair with this repertoire. For generations, the first Gilbert and Sullivan in the theatre has been an iconic experience. I’ve lost count of the number of people who’ve told me that ‘My aunt took me to see Pinafore or Pirates or The Gondoliers when I was eight’ – and how that got them hooked on G&S. It’s become a primal theatre experience for many of us.

And with our new production of The Gondoliers, when we’re able to stage it, we look forward to building a whole new army of converts. With all our entertainment options today, G&S is no longer the go-to for schools and amateur productions. This is no bad thing. We now have the opportunity to reinvent and reassess this repertoire without the weight of a century of performance practice.

At 16, when I was performing my first G&S role, I discovered a book called Martyn Green’s Treasury of Gilbert and Sullivan, which annotated all the librettos. I read it from cover to cover and fell in love with the language – words that you’d never meet in your ordinary life, words that seemed to have been coined simply for the thrill of it, arcane classical references, and countless tarantaras, tiny tiddle toddles and willow walys. Even without hearing the music, I was hooked.

My adoration of Sullivan came a little later: while revelling in the composer’s sprightly, gleeful invention, the Savoy Operas provided my first taste of classical music. Through Sullivan’s extraordinary ablility to satirise, pay homage and celebrate, I discovered a whole world of musical styles from Handel through Donizetti to Verdi, and even a soupçon of Wagner. And yet, as with the best composers, it always sounded like Sullivan: play a few bars and it’s unmistakeable.

The G&S operettas’ durability is extraordinary but not unexplainable. After all, Gilbert’s dramatic situations are still funny. The way in which plots hinge on twins being swapped at birth or ridiculous legal technicalities played like a satire on melodrama to the Victorians, but, let’s face it, stranger things happen on EastEnders and Home and Away. Sullivan’s music succeeds in providing a kind of romantic foil to Gilbert’s pervasive drollery and cynicism. This kind of friction was very much at the heart of Gilbert and Sullivan’s creative relationship – a perfect marriage, complementary and challenging. And they shared a sense of humour. Nothing Sullivan wrote with others holds a candle to the music inspired by Gilbert’s words. What Sullivan did to those words was to sabotage them, and transform them by encasing them in glorious melody.

What other body of work, what other collection of 14 operas, reveals such riches, all of a type, a family, yet all different, thrilling, witty, satirical, gossamer-thin and with real heart? The Savoy Operas’ fusion of gentle satire with genuine, heartfelt emotion is a combination that never ages – indeed, it’s perhaps something we need now more than ever.

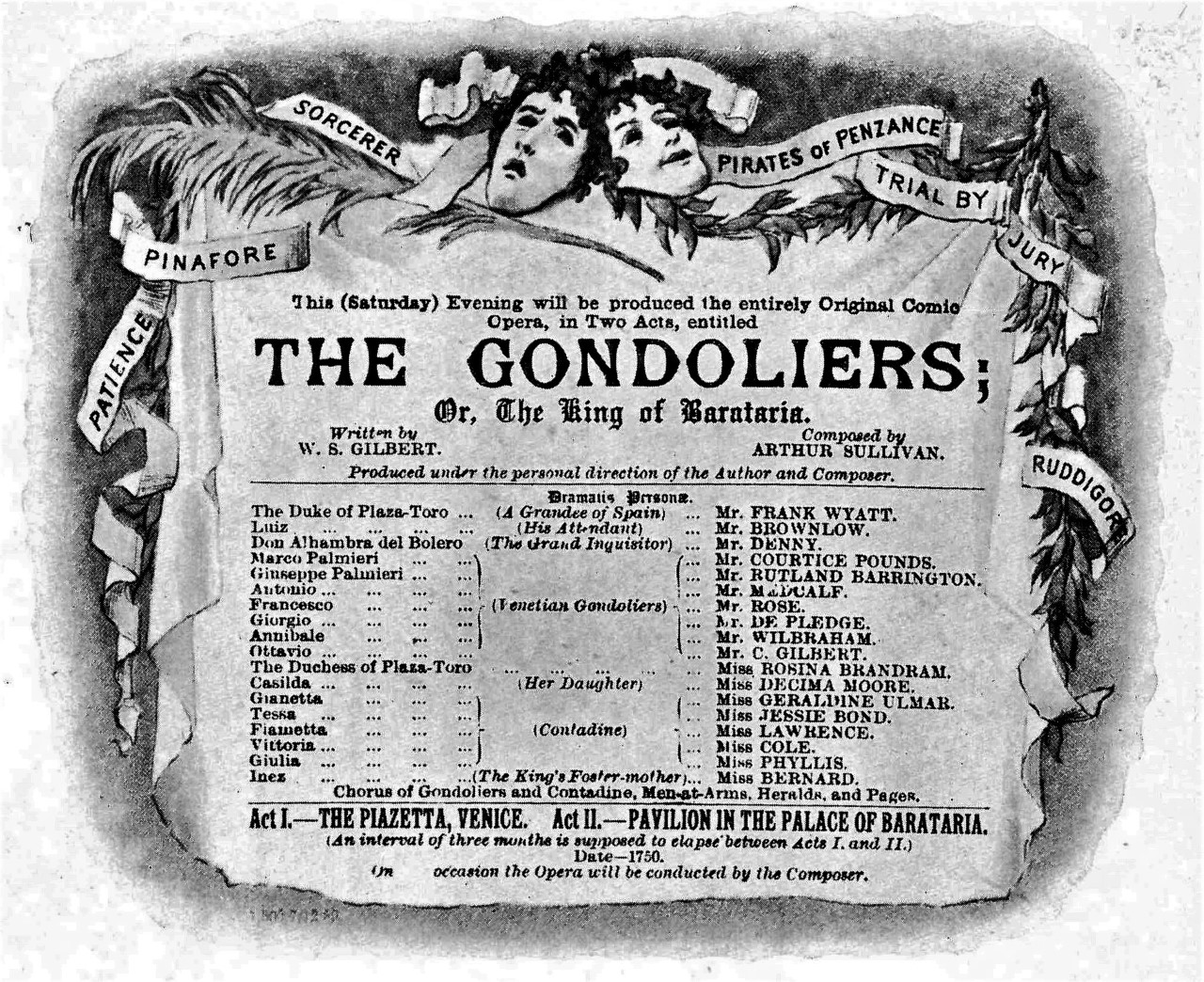

The Gondoliers original cast from the 1891 programme

Decima Moore as Casilda in the original cast of The Gondoliers, 1891

Scene from Act I of The Gondoliers, 1891

Frank Wyatt as the Duke of Plazatoro in the original cast of The Gondoliers, 1891

Rutland Barrington (Giuseppe) and Courtice Pounds (Marco) in the original cast of The Gondoliers, 1891

The Gondoliers performed before the Queen and court at Windsor Castle, from the Daily Graphic, 9 Mar 1891

WH Denny as Don Alhambra in the original cast of The Gondoliers, 1891

Programme Note

Gilbert and Sullivan’s sunniest opera marks the most radiant expression of their distinct yet united talents, as well as the high-water mark in their sometimes fractious professional relationship, as Ian Bradley explains

For such a sunny and successful piece, The Gondoliers had a somewhat difficult and protracted gestation. Sir Arthur Sullivan had found his last collaboration with WS Gilbert, The Yeomen of the Guard, much more to his liking than the earlier and lighter Savoy operas, and it had strengthened his resolve to devote himself to grand opera. When Gilbert approached him about working on another comic opera early in 1889, the composer responded:

"You say that in a serious opera you must more or less sacrifice yourself. I say that this is just what I have been doing in all our joint pieces, and, what is more, must continue to do in comic opera to make it successful. Business and syllabic setting assume an importance which, however much they fetter me, cannot be overlooked. I am bound, in the interests of the piece, to give way. Hence the reason of my wishing to do a work where the music is to be the first consideration – where words are to suggest music, not govern it."

Gilbert replied in equally emphatic terms:

"If you are really under the astounding impression that you have been effacing yourself during the last 12 years… there is certainly no modus vivendi to be found that shall be satisfactory to both of those of us. You are an adept in your profession, and I am an adept in mine. If we meet, it is to be as master and master – not master and servant."

A rather fractious correspondence ensued, which gradually became less acerbic, thanks partly to the intervention of Richard D’Oyly Carte, the impresario who had brought Gilbert and Sullivan together. He suggested that Sullivan might work on a grand opera with a different librettist while collaborating on another lighter work with Gilbert.

Venetian inspirations

A holiday in continental Europe, which took in Venice, improved Sullivan’s mood, and when he returned home in April 1889 he responded positively to Gilbert’s suggestion of a Venetian setting for a typically topsy-turvy plot involving Republican-inclined gondoliers finding themselves jointly ruling an island kingdom. Both men spent longer creating The Gondoliers than they had on any of their previous 11 joint works (including Thespis, their first collaboration, back in 1871). Gilbert took the best part of five months to write the libretto, and Sullivan was occupied on the music for the whole of the summer of 1889, which he spent largely at Weybridge in Surrey. He received the songs one or two at a time, and numerous letters passed between composer and librettist about redrafting or dropping particular numbers once the overall structure of the work became clearer.

Despite this comparatively long period of preparation, the run-up to the opening performance was a frantic rush. Sullivan did not have his first orchestral rehearsal until five days before the London first night. After taking the rehearsal, he dined at home and then worked until three the following morning composing the Overture. He was up again after only a few hours’ sleep to agree with Gilbert the title of the piece – which had, characteristically, been left to the last minute. Two days later, the dress rehearsal lasted for a marathon seven hours.

The Gondoliers opened at the Savoy Theatre on the Strand on 7 December 1889, and ran for 559 performances until 20 June 1891. The critics were almost unanimous in their praise, with the Daily Telegraph applauding ‘the all-pervading character of brightness and unaffected delight’ and noting: ‘The Gondoliers conveys an impression of having been written con amore. It is as spontaneous as the light-hearted laughter of the sunny South and as luminous as an Italian summer sky.’

The public’s reaction was equally ecstatic. When Chappell’s published the vocal score, 12 men were employed packing it from morning till night, and on the first day alone, 20,000 copies were dispatched in 11 wagonloads. One evening, Sullivan was watching a performance from the back of the dress circle and found himself humming the melody of one of the songs. An elderly gentleman standing next to him said angrily, ‘Look here, sir, I paid my money to hear Sullivan’s music – not yours.’

In the United States the reception was markedly cooler, and its lack of success of the box office earned the opera the nickname The Gone Dollars. This contrasting appeal on either side of the Atlantic has continued ever since. Though in Britain The Gondoliers has always been in the top four Savoy operas in terms of popularity (alongside The Mikado, The Pirates of Penzance and HMS Pinafore), in the United States it has never attained this status, perhaps because it is the least English of Gilbert and Sullivan’s works, and therefore not as appealing to the Anglophile sentiments of their North American fans.

Short-lived unity

Nevertheless, the opera’s success in Britain inspired from both composer and librettist rare but heartfelt tributes to each other’s talents. Sadly, this relatively unusual state of librettist and composer acting, like Marco and Giuseppe Palmieri, ‘in perfect unity’ was to be short-lived. Shortly after the opening of The Gondoliers, Gilbert set off on a cruise to India with his wife. When he returned home, he was appalled to discover that £4,500 of the partners’ money had been spent on preliminary expenses for the opera, including a sum of £500 for new carpets for the Savoy Theatre. He exploded at D’Oyly Carte, who responded by saying: ‘Very well, then – you write no more for the Savoy Theatre.’

The ‘carpet quarrel’ soured relations between librettist and composer for the next two years. Both went their separate ways and found new collaborators. Sullivan at last fulfilled his desire to be a composer of grand opera, writing a work based on Sir Walter Scott’s novel Ivanhoe that on 31 January 1891 was the opening production at the brand new Royal English Opera House (now the Palace Theatre in London’s Cambridge Circus), which Carte had built as the home for what he hoped would be a new English school of grand opera. Gilbert collaborated with composer Alfred Cellier on The Mountebanks, about a magic potion that causes those who have taken it to become what they have pretended to be, which opened at the Lyric Theatre on 4 January 1892.

Although Gilbert and Sullivan did bury the hatchet and come together again for Utopia, Limited in 1893 and The Grand Duke in 1896, neither work achieved the success of their earlier collaborations. In many ways, The Gondoliers marks the culmination and high-water mark of their work together, and stands as the supreme expression of their distinct yet united talents. Gilbert’s libretto manages to pack a considerable satirical punch without being either heavy-handed or overtly silly. It also allowed Sullivan to achieve his object of making his music more dominant than it had been in their earlier works. The Gondoliers has the longest vocal score of any of the Savoy operas, including the three-act Princess Ida.

What to listen out for

Lengthy opening sequence: The chorus ‘List and learn’ begins a sequence of music that continues, uninterrupted by dialogue, for more than 18 minutes. It is the longest opening sequence, and very nearly the longest continuous passage of music, in any of the Savoy operas, being beaten only by the Act I finale of Iolanthe. Sullivan revels in the Venetian setting to produce a non-stop sequence of gorgeous melodies. There is a distinctly Italian feel to the whole sequence, with more than an echo of Rossini.

Similarity with well-known tunes…: Sullivan was sometimes accused of borrowing rather heavily from existing tunes. Several critics detected a strong resemblance between the opening bars of Tessa’s Act I aria ‘When a merry maiden marries’ and the refrain ‘Just a song at twilight’ from the popular parlour ballad ‘Love’s Old Sweet Song’, composed by James Molloy. When this was put to him, Sullivan retorted, ‘I do not happen to have heard the song, but even if I had, you must remember that Molloy and I had only seven notes on which to work between us.’

… and quotations of familiar tunes: Another favourite device of Sullivan is the insertion of snatches of well-known folk or national airs in the middle of his more comic songs. Don Alhambra’s Act II aria, ‘There lived a king’, provides good examples of this in the scoring that accompanies Marco and Giuseppe’s reprises of the lines in the middle of each verse. ‘With toddy, must be content with toddy’ has an accompaniment that suggests the droning of bagpipes at the start of a reel, in a nod to the Scottish associations of the whisky-based drink. The singing of ‘With admirals around their wide dominions’ is scored with a snatch of hornpipe. Sullivan originally provided an accompaniment to the line ‘Of shoddy, up goes the price of shoddy’ that quoted a few bars of ‘Yankee Doodle Dandy’. According to Courtice Pounds, the tenor who created the role of Marco, this was inserted to show what the composer thought of American pirate versions of the Savoy operas. However, on hearing it at a rehearsal, Sullivan’s American lover, Fanny Ronalds, apparently protested that it might offend her compatriots, and Sullivan promptly removed this particular musical joke.

Act I finale: The sunny atmosphere spreads across the Act I finale, which is unusual in a Savoy opera in not involving a dramatic confrontation or revelation. Its most exuberant number, the quartet ‘Then one of us will be a Queen’, had Queen Victoria enthusiastically tapping her feet during a command performance at Windsor Castle in 1891. Sullivan revelled in capturing the emotional aspects of the impending separation of the newly-wed gondoliers from their wives, and scoring what is essentially a protracted farewell with elements of both rejoicing and regret. The barcarole-like final chorus, ‘Then away we go to an island fair’ – based on the rowing rhythm of traditional Venetian boat songs – is as lilting and sensuous as anything Sullivan wrote, and perfectly conjures up the enchanted atmosphere of a Mediterranean seascape.

Setting different vocal themes against each other: Running two very different musical themes against each other is often seen as one of Sullivan’s trademarks. He famously does it in the double choruses in The Pirates of Penzance and The Yeomen of the Guard, while in the trio ‘To sit in solemn silence’ in The Mikado he has three different themes running concurrently. In a letter to a friend about his use of this technique, he wrote: ‘The most ingenious bit of work (certainly the most difficult) is the quartet in The Gondoliers, “In a contemplative fashion”.’ It is certainly one of his most complex and carefully constructed ensembles, with the characters basically sustaining a slow, quiet melody but periodically interrupting its flow with rapid and angry solo outbursts, and reaching a powerful climax of clashing confusion before a calm return to the basic opening melody with the conclusion ‘Quiet calm deliberation disentangles every knot’. Both composer and librettist laboured over this more than over any other number in the opera, with Gilbert having to produce several drafts to satisfy Sullivan. It has been likened to Haydn’s humorous serenade Maiden Fair, O Deign to Tell, although the predominant influence is surely Italian, with echoes of Donizetti and Rossini once again.

Ian Bradley is Emeritus Professor of Cultural and Spiritual History at the University of St Andrews, and author of The Complete Annotated Gilbert & Sullivan

(Oxford University Press).

Venice in Music

From the sunshine sparkling on The Gondoliers’ Venetian canals to the glories of the Baroque and darker, more modern evocations, Jessica Duchen ponders the enduring inspirations that composers have drawn from La Serenissima

Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Gondoliers is really a satire on matters closer to home than Venice. Still, could it have existed without the musical world’s perennial fascination for La Serenissima? ‘When I seek another word for “music”, I never find any other word than “Venice”,’ wrote Friedrich Nietzsche in Ecce homo.

Over the centuries, this unique city, precariously balanced on 118 islands, has exerted a powerful attraction thanks to its mysterious canals, rose-coloured Renaissance palaces and waterborne transport – especially the sleek, black gondolas steered by supposedly singing boatmen. Yet maybe the most fascinating thing about the city’s musical inspirations is the way they have evolved over the centuries, from sunlit splendour towards images of unease and decay.

At the heart of it all stands the Basilica of San Marco. It’s a unique building with burnished-gold Byzantine mosaics across its arches, and two choir lofts facing each other – an architectural quirk that proved irresistible to the composers of the 16th and 17th centuries. Giovanni Gabrieli, whose music is the epitome of the Renaissance Venetian school, set this space ringing with groups of singers or players in opposite balconies, creating musical conversations – as had his uncle, Andrea Gabrieli, before him. Claudio Monteverdi, having created his famous operas for the court of Mantua, became head of music at San Marco in 1613. His 1610 Vespers had shown everyone exactly what he could do, and since there was nothing that this peerless composer couldn’t achieve in terms of musical expression and invention, the results remain breathtaking four centuries later.

Sixty years after Monteverdi’s death, a young Venetian priest who was also a violinist started on an unconventional path to celebrity. Had he lived in the 21st century, Antonio Vivaldi might have been running a music organisation’s education department. As it was, as musical director of an orphanage called the Ospedale della Pietà, the ‘Red Priest’ – as he was known because of his flame-coloured hair – transformed a group of girls into one of Venice’s most prized musical ensembles, and composed for them concertos that are still played today the world over. Unfortunately for Venice, The Four Seasons were not among them (he wrote that quartet of concertos later, in Mantua). But in the meantime, he also became the impresario of Venice’s Teatro San Angelo and eventually developed this sideline into an output of a good 50 operas.

It was no wonder that the city’s magnetism extended to composers from further afield, and in 1709 an Italian opera by a young German composer took the place by storm. Georg Friedrich Händel’s Agrippina ran for 27 successive nights at the Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo, and soon the ecstatic Venetians were calling its composer ‘Il caro Sassone’. Having assimilated the techniques of Italian opera, this ‘beloved Saxon’ soon imported it – and some of its finest exponents – to England, where he lost his umlaut and gained his own opera company, among much else.

Gondola songs sweep the world

If the outward aspect of Venice had exemplified Renaissance and later Enlightenment ideals of beauty, proportion and civilisation – to say nothing of the luxury enabled by its exceptional wealth – the Romantics were magnetised by other qualities. ‘Venice, its temples and palaces did seem like fabrics of enchantment piled to heaven,’ wrote Percy Bysshe Shelley. Its sheer romance was taking over as prime attraction, and diffusing quickly through the music of other lands.

Felix Mendelssohn’s Songs without Words targeted the exploding market in the 1830s and 40s for music targeted at keen amateur pianists. Among his best-known are two that are popularly nicknamed ‘Venetian Gondola Songs’. Their rhythms suggest the ebb and flow of waves and the rocking of boats, and their melodies are Italianate in bel canto fashion. He appears to have been one of the first to bring this concept to the piano.

Going further still, Frédéric Chopin took up the idea and transformed it into a masterpiece. His Op. 60 Barcarolle (another name for a gondolier’s song) is a ten-minute treasure trove of exquisite piano writing, full of the influence of the bel canto opera he loved. Gabriel Fauré much later composed 13 barcarolles for piano, some of which are likewise miniature (and sometimes not so miniature) tone-poems.

Still, one of the most famous of all barcarolles is by Offenbach. It opens the ‘Giulietta’ act of his opera The Tales of Hoffmann, in which a seductive courtesan, vampire-like, steals the hero’s reflection. The barcarolle, sung as a duet, with its hypnotically undulating melody, at once encapsulates the mystery ahead and suggests a superficial beauty that conceals demonic forces at work beneath.

Darkness and mystery

It’s worth noting, however, the irony that although the Venetian gondola song came to symbolise a certain popular notion of Italian music, Venice was for a long time not technically Italian at all. For centuries it was an independent republic, with a language dialect of its own. Only after the Napoloenic Wars and the 1814 Congress of Vienna was it swallowed up into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It finally joined the Kingdom of Italy as late as 1866.

Alongside the splendour and drama, however, there’s a distinctly dark side to certain works associated with Venice, perhaps partly because of the city’s necessarily unique approach to funerals. Burial is not an easy prospect in a place surrounded by water and latticed with canals. Therefore the lagoon island of San Michele became cemetary to the city, and coffins could only be transported there by boat. In 1882, the elderly Franz Liszt witnessed a floating funeral procession on the Grand Canal and experienced a premonition that his son-in-law and colleague Richard Wagner would die there, an incident that inspired his intense and uncompromising late piano piece La lugubre gondola. Sure enough, the following year Wagner suffered a fatal heart attack while staying in Venice. His body was transported by gondola to the railway station before its return home to Bayreuth.

Perhaps these grim events were the start of the 20th century’s association between Venice and things that are far more sinister than gondola songs. The 17-year-old Erich Wolfgang Korngold set his 1916 one-act opera Violanta in Renaissance Venice. A tragic love story with a psychological twist, it’s rich with claustrophobic atmospheres and Technicolor orchestration, evoking a world of both opulence and violence.

Thomas Mann’s 1912 novel Death in Venice captured public imagination long before it was transformed into a film by Luchino Visconti in 1971. A large proportion of the movie’s decadent atmosphere is created by its soundtrack, chiefly the Adagietto from Mahler’s Fifth Symphony. Benjamin Britten took a totally different approach when writing an opera based on the book two years later, creating perhaps his edgiest stage work. Through the 20th century, authors continued to associate Venice with sinister or threatening turns of fate rather than romance. Daphne du Maurier’s story Don’t Look Now (made into a film by Nicolas Roeg in 1973) and Ian McEwan’s The Comfort of Strangers are cases in point – and either could make (hint, hint) a stunning opera.

Nevertheless, composers remained alive to La Serenissima’s wonders – Venice-born Luigi Nono in particular, who spoke of its sonic ‘magic and mystery’. In a radio interview about ten years ago, his widow, Nuria Schoenberg, recalled that the city had helped to make Nono conceive music as ‘a 360-degree elemental immersion’. His 1976 work … sofferte onde serene… for piano and tape is filled with the bells and atmospheres of the city.

Venice found itself in the spotlight during the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, as wildlife in the form of fish and nesting birds made a sudden return to its canals and walkways in the absence of tourists and water vehicles. Yet quite apart from the impact of the virus, Venice today is in existential peril, its landmarks threatened by rising sea levels, its residents’ lives wrecked by excessive tourism. If it has a role in 21st-century opera, it may well be as a symbol of ecological disaster, as a once great civilisation doomed to sink beneath the waves. It offers a stark contrast with the sunshine of Gilbert and Sullivan’s gondoliers. In their world, Venice was still carefree, exotic and as ripe a setting for witty political pilloring as any location upon which their merciless imaginations made landfall. Let’s enjoy it while we can.

Author and music critic Jessica Duchen has written for the Independent, the Observer and the Sunday Times. Her most recent novel is the

Beethoven-themed Immortal.

Biographies

Derek Clark – Writer/Presenter/Pianist

Derek Clark was born in Glasgow and studied at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama, Durham University and London Opera Centre. He joined Welsh National Opera’s music staff in 1977 as a repetiteur and staff conductor, and joined Scottish Opera as Head of Music in 1997.

Scottish Opera appearances: Samson, The Magic Flute, Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, Così fan tutte, The Barber of Seville, The Italian Girl in Algiers, The Elixir of Love, Fidelio, Rigoletto, Il trovatore, La traviata, Macbeth, Falstaff, Orpheus in the Underworld, The Pirates of Penzance, The Mikado, Carmen, Manon, La bohème, Tosca, Madama Butterfly, Eugene Onegin, Hansel and Gretel, The Burning Fiery Furnace, Inés de Castro, Five:15 (2008-10), The Lady from the Sea by Craig Armstrong – world premiere, Clemency by Sir James MacMillan – Scottish premiere, The Trial by Philip Glass – Scottish premiere. He also appeared with Jamie MacDougall in Lauder, and has devised 23 Opera Highlights/Essential Scottish Opera programmes. He provided reduced orchestrations for small-scale tours of Hansel and Gretel, La Cenerentola, Die Fledermaus, Rodelinda and L’elisir d’amore, and the musical reworkings for the highly successful annual Pop-up Opera tours.

Besides his work as accompanist, coach, arranger and composer, he has assisted Sir Roger Norrington and Richard Egarr at the Edinburgh International Festival and is Musical Director of the Dundee Choral Union.

Sioned Gwen Davies – Mezzo-soprano

Born in Colwyn Bay, North Wales, Sioned Gwen Davies studied at London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama and National Opera Studio. She represented Wales at the 2017 BBC Cardiff Singer of the World Competition. Among her awards, she won first prize at the 2009 Llangollen International Musical Eisteddfod, and first prize at the 2009 National Eisteddfod of Wales. She was a Scottish Opera Emerging Artist in 2013/14.

Scottish Opera appearances: Kate The Pirates of Penzance, Opera Highlights 2015, Eduige Rodelinda, Lady in Waiting/Second Witch Macbeth, Marta Iolanta, Third Dryad Rusalka, Pitti-Sing The Mikado, Stewardess Flight, Olga Eugene Onegin, Maddalena Rigoletto, Third Lady The Magic Flute, Second Secretary to Mao Nixon in China.

Operatic engagements include: Tisbe La Cenerentola (West Green House Opera); Pitti-Sing (English National Opera); Margarida The Yellow Sofa by Julian Philips (Glyndebourne); Olga (Valladolid Opera); Second Lady The Magic Flute (Longborough Festival Opera)

Ellie Laugharne – Soprano

Soprano Ellie Laugharne studied at Birmingham University, the Birmingham Conservatoire and London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama. She has been a Jerwood Young Artist at Glyndebourne and an Associate Artist at Opera North, and she is also a Samling Artist and an Associate Artist with Classical Opera.

Scottish Opera appearances: Mabel The Pirates of Penzance, Frasquita Carmen, Adina L’elisir d’amore.

Operatic engagements include: Susanna The Marriage of Figaro, Lucia The Rape of Lucretia (Glyndebourne on Tour); Susanna (The Grange Festival); Phyllis Iolanthe, Barbarina The Marriage of Figaro, Cupid Orpheus in the Underworld, Frasquita (English National Opera); Governess The Turn of the Screw, Tina Flight, Zerlina Don Giovanni (Opera Holland Park); Despina Così fan tutte, Gretel Hansel and Gretel, Susanna (Opera North); Sandrina La finta giardiniera, Edna Tobias and the Angel (Buxton Festival).

Ben McAteer – Baritone

Born in Northern Ireland, baritone Ben McAteer studied at London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama, and National Opera Studio.

Scottish Opera appearances: Guglielmo Così fan tutte, Figaro The Marriage of Figaro, James The Devil Inside, Pish-Tush The Mikado.

Operatic engagements include: Falke Die Fledermaus, Goryanchikov From the House of the Dead (Welsh National Opera); Papageno The Magic Flute, Eisenstein Die Fledermaus, Marullo Rigoletto (Northern Ireland Opera); Sharpless Madama Butterfly (Opera Holland Park); Marcello La bohème (Lyric Opera Ireland); Earl of Mountararat Iolanthe (English National Opera); Count Almaviva The Marriage of Figaro (Irish National Opera); Father Hansel and Gretel (Irish National Opera, Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre).

William Morgan – Tenor

British tenor William Morgan studied at London’s Royal College of Music and National Opera Studio, and is an English National Opera Harewood Artist.

Scottish Opera appearances: Tamino The Magic Flute, Misael The Burning Fiery Furnace, Opera Highlights Autumn 2017 and Spring 2018, The 8th Door.

Operatic engagements include: Tom Rakewell The Rake’s Progress (Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra); Writer Jack the Ripper: The Women of Whitechapel by Iain Bell – world premiere, First Priest The Mask of Orpheus, Reporter Orphée by Philip Glass, Younger Man Between Worlds by Tansy Davies – world premiere, Peter Quint The Turn of the Screw, Hot Biscuit Slim Paul Bunyan, Phaeton The Day After by Jonathan Dove (English National Opera); Don Ottavio Don Giovanni, Anthony Hope Sweeney Todd (Longborough Festival Opera); Falstaff (Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra); Pastore/Spirito L’Orfeo (Bavarian State Opera); Spoletta Tosca (Nevill Holt Opera); Cervantes The Queen’s Lace Handkerchief by Johann Strauss II (Opera della Luna); Hippolyte et Aricie (Glyndebourne); Antonio Das Liebesverbot (Chelsea Opera).