Spotlight on...

Candide

Scottish Opera staged Leonard Bernstein’s Candide in 1988, in a new version created by Bernstein’s protégé and friend John Mauceri, the Company’s Music Director at the time, in collaboration with the composer.

Bernstein’s operetta, based on the satirical 1759 novella by Voltaire, had opened on Broadway in 1956, but the original production was not a success. Following a London production in 1959 and revivals in the US by Hal Prince, Bernstein created a two-act version for opera companies in 1982, premiered by New York City Opera.

For the 1988 Scottish Opera staging, Bernstein worked with John Mauceri on a version that would convey his final wishes. Both writers of the operetta’s earlier books – Lillian Hellman and Hugh Wheeler – had died since the work’s earlier stagings, and British writer and satirist John Wells was asked to write an entirely new book for the new version.

Bernstein attended rehearsals in Glasgow, and the production of what has come to be known as the ‘Scottish Opera Version’ opened on 19 May 1988, directed by Jonathan Miller, and recorded for BBC broadcast the same year. It ran for 14 performances in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Newcastle and Liverpool, before transferring to London’s Old Vic, where it won two Olivier Awards.

Candide 1988

Music by Leonard Bernstein. Book adapted from Voltaire by Hugh Wheeler. Lyrics by Richard Wilbur with additional lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, John Latouche, Lillian Hellman, Dorothy Parker and Leonard Bernstein. Orchestrations by Leonard Bernstein and Hershy Kay. Additional orchestrations by John Mauceri. Adapted for Scottish Opera by John Wells and John Mauceri.Cast

Voltaire/Pangloss/Cacambo/Martin

Nickolas Grace

Governor/Captain/Gambler

Bonaventura Bottone/David Hillman

Candide

Mark Beudert

Cunégonde

Marilyn Hill Smith/Andrea Bolton

Old Lady

Ann Howard

Paquette

Gaynor Miles

Maximilian

Mark Tinkler

Baron/First Officer/Grand Inquisitor/First Jesuit/Slave Driver/Ragotski

Leon Greene

Don Issacher/Jew/Father Bernard/Anabaptist/Second Officer/Sage

Howard Goorney

Baroness/Waitress

Elaine MacKillop

Lisbon Woman/Waitress

Carol Rowlands

Informer/Announcer/Aide

John Brackenridge

Huntsman/Croupier

Paul Anwyl

Waiter

Tom McVeigh

Lisbon Man

David Morrison

King Achmet

Declan McCusker

Prince Charles Edward

Grant Richards

Czar Ivan/Sailor

Graeme Danby

King Herman

Jonathan Hawkins

King Stanislas/Archbishop

Scott Cooper

Creative Team

Conductors

John Mauceri

Justin Brown

Directors

Jonathan Miller

John Wells

Designer

Richard Hudson

Lighting Designer

David Cunningham

Choreographer

Anthony Van Laast

Scottish Opera Orchestra

Scottish Opera Chorus

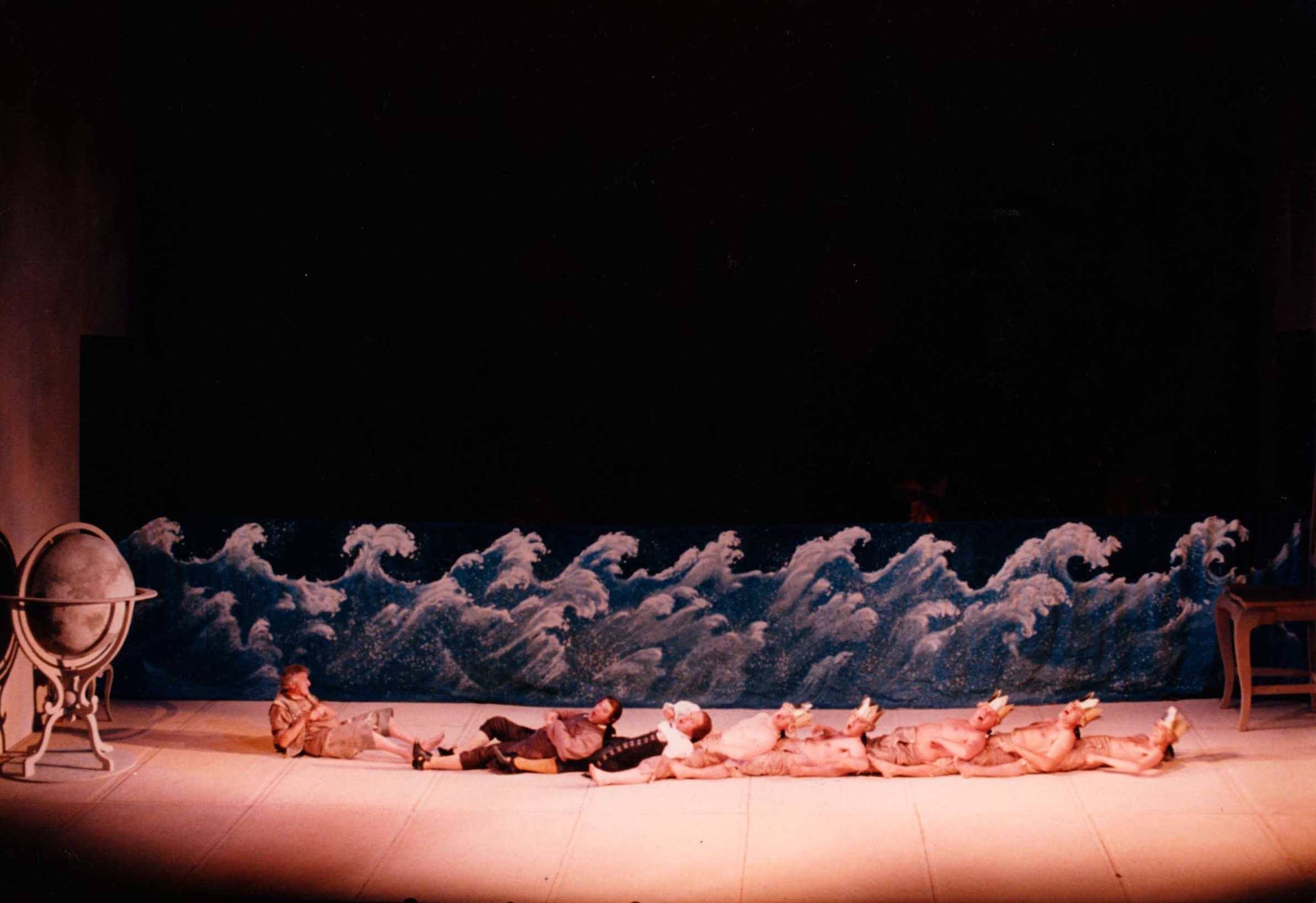

The Cast of Candide, credit Eric Thorburn 1988

The Cast of Candide, credit Eric Thorburn 1988 (1)

The Cast of Candide, credit Eric Thorburn 1988 (2)

Richard Mantle, Leonard Bernstein & Sir Jonathan Miller in rehearsals for Candide, credit Eric Thorburn 1988

Richard Mantle, Leonard Bernstein & Sir Jonathan Miller, credit Eric Thorburn 1988

Synopsis

Candide is in love with Cunégonde, daughter of the house in Westphalia where he is brought up. Dr Pangloss, their tutor, teaches them that everything in this world is for the best, and part of God’s universal plan.

Candide is then subjected to a knockabout series of disasters to test this theory. He is expelled from Cunégonde’s home; press-ganged into the army; he finds Cunégonde raped and apparently dead; and he meets Pangloss disfigured by syphilis. Surviving an earthquake, they are captured by the Holy Inquisition, and Pangloss is hanged.

Reunited with Cunégonde, he kills her new lovers and they flee together to South America, where she is sold into slavery. After many adventures among war-like Jesuits and the wise inhabitants of the lost world of El Dorado, he returns to Venice where he finds Cunégonde a prostitute in a gambling casino.

Finally disillusioned, Candide realises that the world is neither good nor bad, but what we make of it.

Candide Revisited

Conductor and Scottish Opera Music Director John Mauceri introduces the new version of Bernstein’s problematic masterpiece that he created for Scottish Opera, in an article from the original 1988 programme

When On Your Toes opened on Broadway in 1983 with its original orchestrations, arrangements and complete score (as well as its original director and choreographer from its first appearance in 1936), few people seemed willing to support the concept of the integrity of the Broadway score. The songs were never in doubt, of course – provided you could add a few extra hits to a revival – but never had anyone dared to keep the dance arrangements and orchestrations intact. The wisdom of the time was to write new ones. (This, of course, still unfortunately happens, as with London’s recent Kiss Me Kate, which jettisoned all the original dance music and replaced it with new music and totally new orchestrations. Certainly more than 40% of the evening’s music is composed/arranged by someone other than Cole Porter.)

Kiss Me Kate was at least a hit in 1946. Butt what of the flops? What if Puccini had thrown out Madama Butterfly after his opening-night fiasco? Or Verdi with La traviata? Puccini and Verdi were fortunate in that they lived in an era that gave the composer a second or third chance. This rarely happens today in the world of opera and music theatre.

When Candide opened on Broadway in 1956, it was not a success. Its out-of-town tryout in Boston was unhappy. (The staid people of Boston can still recall Tyrone Guthrie’s pre-curtain speech begging their indulgence by telling them: ‘Keep your peckers up!’) The work was called a ‘comic operetta’ but there was nothing funny in Lillian Hellman’s book. It was ponderous and pedagogical, springing more from her anger at the McCarthy trials than from any attempt at representing Voltaire. While Leonard Bernstein had captured the spirit of the French book, the American playwright seemingly had no intention of doing anything of the kind.

Opera singers played the major roles, except for actor Max Adrian as Pangloss and a young and inexperienced lyric soprano Barbara Cook as Cunégonde. Operatic works had occasionally been tried on Broadway – and rarely with commercial success: Porgy and Bess in the 1930s, Street Scene in the 1940s, and at the time of Candide, Menotti opened The Saint of Bleecker Street and The Consul on the Great White Way. Bernstein’s mentor Marc Blitzstein had adapted Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes for his opera Regina, but again without making money – Broadway’s cruel measure of success.

But Candide would not die. It came to London in 1957 with some new songs, but it did not succeed there either. Until 1971, when Gordon Davidson directed a new production in Los Angeles with the hope of a Broadway run, the Hellman script was adapted and Bernstein was still writing material for poor Candide. The Davidson production got all the way to Washington’s Kennedy Center, but closed there before it could travel five hours north to New York. But it still would not die.

The next year, Hal Prince decided to make a completely new version without one line from Lillian Hellman. The English-born playwright Hugh Wheeler wrote a short and very funny book to accommodate a one-act, cartoon-like version of Candide. This time, Bernstein had no hand in the music, preferring to stay at Harvard for his Norton Lectures and letting me act in loco compositoris, using his music. The puzzle was to fit pre-existing music to a new set of situations and locales.

Armed with two volumes of extra material written from 1956 until 1971, as well as the 1956 published score, I was allowed to play in the garden with Hal Prince and Hugh Wheeler and Stephen Sondheim. It was a magical time for me. Lenny came to the dress rehearsal in Brooklyn, and seemed to love it. He saw it one more time and seemed to hate it. But it was a hit. It sold tickets, and for the first time in Candide’s history, it was making money. After its limited run in Brooklyn, it opened on Broadway, slightly enlarged, but still in one act, and it ran for over a year.

Once it closed, this little and funny Candide became – and still is – an immensely popular property for small theatre companies throughout America. But more than half the score is missing from that version, and its orchestration for 13 instruments is clever but hardly the sound intended by the composer in 1956.

As a stopgap, I arranged a Candide Suite for the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, which contains about 50 minutes of the 1956 score and can be performed by symphony orchestras with four soloists and a chorus. At least this way, more of the original score could be heard. But in 1983, the idea of an expanded performing version based on the Hugh Wheeler script became a reality, in response to enquiries from opera houses to make available a version with greater legitimacy.

This time, Bernstein went to Los Angeles to run a conducting school while I basically completed the task started in 1973 for Brooklyn. The expanded book could accept almost all of the music from Candide, even some songs that had never been orchestrated before. The two-act ‘opera house’ version opened at the New York City Opera and was an immense success – not by Broadway terms, of course, because it only played a very limited run, rather than eight a week, but as an opera it was up there with Carmen and La bohème in popularity in the City Opera’s season. Although the composer was always consulted about this expanded version, and although he was acclaimed on the opening night, and although he was unstinting in his praise for me, I knew him well enough to know that it was still not right. The success was hardly the point. Something had gone out of Candide after 1971 and the composer wanted it back.

It would be facile to say it was guilt over allowing the Hellman book to be jettisoned that caused this malaise. I felt it too, and I am no fan of that original book. It seemed impossible, but after working on this for a third of my life, I found myself suggesting a – hopefully – final version that would redress the problems and even risk failure for the sake of something very important.

Bernstein’s music has always been about one thing: exploring the differences among people, and pleading for tolerance to allow us to live in peace and kindness. This Candide had turned into one long joke. The heart, the tears and the faith – all clearly part of Voltaire’s reason for writing Candide – were nowhere to be found in the post-Lillian Hellman versions. Also the music was all out of order. The music intended to be played in Paris had to be placed in Lisbon, and the New World and Venice music was shifted to Constantinople. With a fresh beginning, using Hugh’s two-act version, I was sure that the venues could be rearranged to come close to the 1956 venues, and then the four missing songs and a chorale – most of this being ‘serious’ music – could be restored, giving a proper balance to the evening. The incredulous composer agreed to another go – but this time he had to come to Glasgow and be available during the months of preparation. Hugh Wheeler agreed to adapt his own script, but then sadly died. Jonathan Miller, our chosen director, suggested John Wells to help adapt the script. And we all re-read Voltaire.

This new version restores much Voltaire to the text of Wheeler, which was already closely aligned to the French original, but now includes moments of Voltairean seriousness. Candide’s lament is placed where the composer always wanted it – near the beginning of the show. (This song, which was cut from the 1956 Broadway production, contains the ‘Cunégonde-theme’ of which there are many subsequent variations in the score.) The Paris music is in Paris, the Venice music takes place in Venice. ‘We are Women’, written for London, is restored for the first time in 31 years. ‘Nothing More than This’, written in the 1950s, is restored to the score and placed where the composer intended it – a kind of Alfredo aria in which Candide throws the gold at Cunégonde and leaves her. ‘Martin’s Laughing Song’, written in 1971, is a major restoration since it balances Pangloss’ ‘Best of All Possible Worlds’. From the entrance into Venice to the end of the play, the musical numbers flow with almost no dialogue through to the glorious finale.

We have risked upsetting the success of the opera-house version because Candide is a more complex work, one that aims higher. What better place to try this out than Glasgow?

Memories of Candide

Jay Allen, Principal Percussionist, The Orchestra of Scottish Opera

(Now Scottish Opera’s Orchestra & Concerts Director)

‘It’s always very special to work with a living composer, but to have worked with Leonard Bernstein was a truly memorable and very special time in our lives. Now, more than 30 years later, I realise how very fortunate we all were.

‘A diminutive figure, chain smoking and with boundless energy and exuberance, Lennie entered our rehearsals of Candide, under the guardianship of his protégé John Mauceri. It was clear that there was a deep and strong bond between them. His observations of the orchestral playing were complimentary and very supportive.

‘I remember during one of the rehearsal of ‘Glitter and be Gay’, I agonised about suggesting the addition of a shaker to the middle section, and eventually mustered the courage to play my unwritten addition. To my surprise and even greater relief, Bernstein liked it, and it was added to my part. I would not have dreamt of doing something like that in normal circumstances, but he created such an atmosphere of positivity that we all felt enabled.’

Paul Anwyl, Huntsman/Croupier and chorus member

‘I remember Leonard Bernstein’s visit very well indeed. He was a very direct and rather earthy man, and a lot of the anecdotes would not be printable!

‘We were all very excited when we knew he was coming to Glasgow. We didn’t actually rehearse with Bernstein except for one 15-minute period when he turned up unexpectedly. The chorus singers were delighted to work with him, even for such a short amount of time, and everyone tried their utmost to give him what he wanted. We didn’t see him a great deal during the rehearsal period but kept receiving messages in his inimitable and earthy style that he was enjoying the production. His presence was unbelievably energising and inspiring. He very much liked the production.

‘It was a very complicated show and consisted of many small scenes and numerous small roles that often required different costumes or even a change back into a previous costume. I think it must hold the record for the most costume changes in Scottish Opera’s history: I alone had something like 20 costume changes. I remember one particular change into a denizen of El Dorado wearing a golden toga: I ran off stage, where the dresser was waiting to wrap me in a large piece of gold cloth once I’d thrown off my previous costume. One night the dresser forgot to put the safety pins in the golden toga, which I only realised when I returned to the stage. I could feel it slipping down throughout the scene in which we had to remain very still and statuesque. I managed to keep the garment on by clamping my elbows to my sides but it was one of the longest ten minutes of my life.

‘I remember having to sing in a solo quartet chorale towards the end of the opera, which was put in at the last minute. Apparently John Mauceri had found the chorale in a trunk in Bernstein’s home, and liked it so much that he wanted to include it. Candide was one of several very successful American operas and shows we performed during John Mauceri’s tenure as Music Director. They included Street Scene by Kurt Weill, Regina by Mark Blitzstein and concert performances of Girl Crazy by Gershwin and Lady in the Dark by Weill. John was superb in this repertoire and had a peerless knowledge of the style and scores.’

Richard Mantle, Scottish Opera Managing Director 1985-91

‘Candide is a wonderful piece, but it is fraught with problems. It never seems to work with the public. It’s a crazy story that needed sorting out, really. It’s a minefield of rights and negotiations. John Mauceri wanted to create a new book – not lyrics, which were sacrosanct – so we asked John Wells to write it, and Jonathan Miller to direct. John wrote the book and we were summoned to the USA to read it to Leonard Bernstein. John read the book to me on the plane over, doing all the voices, and I was in tears of laughter. When we arrived we were driven up to Connecticut and read it through to Bernstein in his house. Two things I remember: the piece has two so-called ‘Syphilis Songs’. When he’d heard them, Bernstein rushed over to his piano stool and got out some music. It was a third ‘Syphilis Song’ that he wanted to be included. After dinner and much drink, he began to read to us the Psalms of David. Extraordinary! Then he came to Glasgow for rehearsals. We had a glamorous opening night and transferred to the Old Vic in London. It was great to be involved with those people.’

David Morrison, Lisbon Man and chorus member

‘It was very exciting working with someone of the international fame of Leonard Bernstein, and I’d heard that aside from music he loved people – which became immediately evident. I remember he’d go up to anybody standing alone, introduce himself as Lennie Bernstein, and ask who they were and what they did. We waited on stage after curtain down at his request as he wanted to thank us all. None of us expected his thanks to be individual, but some were quite taken aback when it included a big kiss and a hug.

‘Ian Forth, one of my fellow chorus members, was asked to chauffeur Bernstein during his visit, because he wanted to see as much of Scotland as he could. Bernstein soon wanted Ian with him all the time: every day they’d go out, and Ian had to mug up as much as he could beforehand – Bernstein’s mind was so active that he asked questions constantly, and kept catching Ian off guard.’

Christopher Stearn, trombonist, The Orchestra of Scottish Opera

‘I remember sitting in the pit around an hour before the show that was going to be recorded, just warming up. A guy came into the pit and sat next to me. It was pretty dark and I didn’t see who he was – I thought it was maybe a sound guy. He started asking what I thought about the piece and I was most enthusiastic, then he asked how I enjoyed working under John Maureri, and again I was most enthusiastic. He said he’d known John for many years. I turned and looked at this person asking so many questions and realised that I had been speaking with the producer Humphrey Burton.’

Video: Make Our Garden Grow

From Candide, originally filmed for Scottish Opera's Memory Spinners groups, those living with Dementia, to enjoy at home.Leonard Bernstein

A world-renowned composer, conductor and educator throughout his entire adult life, with a famously larger-than-life personality, Leonard Bernstein conducted major orchestras right across the world (as well as being the New York Philharmonic’s Music Director from 1958 to 1969), and brought together classical music, popular styles and theatrical panache in works across every genre. In musicals such as On the Town, Wonderful Town and West Side Story, or his three symphonies, or much-loved works including Chichester Psalms and the Serenade, after Plato's Symposium, he actively brought together eclectic musical styles with remarkable energy and flair. A committed music educator, Bernstein played an active role in the Tanglewood Music Festival from its founding in 1940, and won awards for his influential televised Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic.

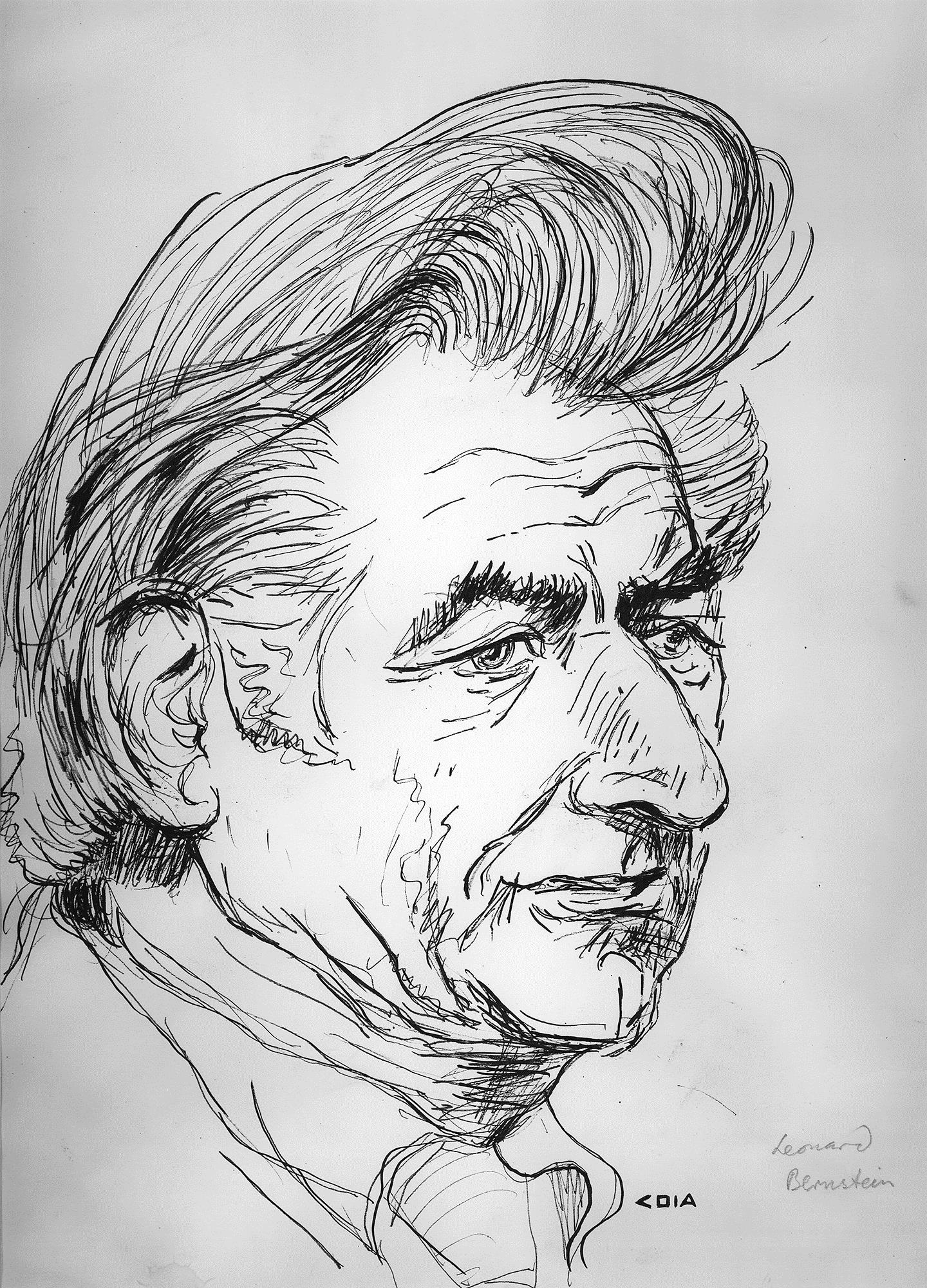

Cartoon drawn in rehearsals by Glaswegian caricaturist Emilio Coia, 1988

John Mauceri

Born in New York, John Mauceri was Scottish Opera’s Music Director from 1986 to 1992. Through his varied and wide-ranging career, he has been a conductor and producer, a university educator and a champion of musical theatre in all its forms. He has worked with opera companies including New York’s Metropolitan Opera, Milan’s La Scala, Turin’s Teatro Regio, London’s Royal Opera House and the Deutsche Oper Berlin, as well as ensembles including the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra. After meeting Leonard Bernstein as a conducting fellow at Tanglewood in 1971, he was invited to be an assistant to the composer, and during his 18-year collaboration, premiered many of Bernstein’s works.

Jonathan Miller

Jonathan Miller was a respected British theatre and opera director, actor, author, television presenter, satirist and medical doctor. As well as Bernstein’s Candide in 1988, he also directed the 1983 production of The Magic Flute for Scottish Opera, which placed Mozart’s singspiel amid towering library shelves in 18th-century Vienna, and was revived in 1985 and 1988. He directed more than 50 opera productions around the world, including a critically acclaimed series for English National Opera, and was knighted in 2002. He died in November 2019.