By Robert Thicknesse

History of Opera

Beginnings: Let’s make an opera

Opera is an ambitious artform. Like all good things it is there to entertain but it is also, even at its most frivolous, deeply serious: it aims to explore, to wonder about the springs of human motivation, to ask the question of all grown-up art, how should we live? And it tries to do this through a combination of factors – music, drama, words, staging, design, movement and the most sophisticated use the human voice has ever been put to – that can seem to be in conflict with each other, each striving for first place. When it works, you really know about it. But what a task. How did it start, and where is it going?

Opera has been around for over 400 years. In the 1580s a group of Florentine intellectuals known as the Camerata thought it would be a good idea to create a mixture of music and theatre along the lines of Greek drama – despite the minor drawback of actually having no idea what Greek drama either sounded or looked like. This was a reaction against current musical trends: they were trying on one hand to correct the inability of polyphonic music – that is, multi-part, often rather austere choral pieces – to properly convey the meaning of words, and on the other to simplify the over-ornateness of madrigals, usually sung by four singers, which had become altogether too flowery for their tastes.

What the members of the Camerata (who included Vincenzo Galilei, Galileo’s father) proposed was a drama featuring a single vocal (‘monodic’) line supported by a simple accompaniment, which would reproduce the rhythms of natural speech and highlight the words: in later times this, or something like it, would become known as recitative. The effect would be of a simply sung or declaimed play. The history of opera is a repeating cycle of this ideal’s gradual corruption by an ever-greater emphasis on purely musical and vocal beauty – as in 18th-century opera seria and the bel canto (‘beautiful singing’) of Bellini and Donizetti – and the attempt to revert to a version of pure first principles, for example in the work of Gluck, Wagner, and to an extent Musorgsky, Janáček and much 20th-century opera.

Monteverdi hits and myths

The process was already at work in the very earliest operas. There were operatic composers before Claudio Monteverdi, but his Orfeo (1607) is among the earliest ever written and certainly the earliest in the regular operatic repertoire. The Greek hero Orpheus is the ideal operatic protagonist, a musician who charms the gods with his singing and his lyre to win back his dead wife Eurydice. What Orpheus sings is already considerably more than the mere ‘heightened speech’ proposed by the Camerata: Monteverdi realised something more musically interesting was required to hold the attention, and the simple declamation often flowers into songs with dancing rhythms and sophisticated instrumental accompaniment. Nonetheless the opera gives us a good idea of the simplicity and directness that was aimed at.

You can see how opera had developed even within Monteverdi’s lifetime by comparing Orfeo with L’incoronazione di Poppea (1643), which blends the ideals of the Camerata (somewhat diluted by this stage) with opera’s greatest obsession, sex (which they call ‘love’). The story describes the frantic and bloody affair between the Emperor Nero and his beloved, the gold-digger Poppea, a love story that doesn’t run smoothly at all. The monodic line is there, but it is mixed in with madrigals and the embryonic form of the aria, a musical soliloquy which was soon to become a vocal showpiece in which the words would have ever decreasing importance. Poppea is much more ‘tuneful’ than the Camerata would have liked, and the linking recitatives have acquired an accompaniment of keyboard, viola da gamba, lutes. The big difference was commercial: opera, by now, was selling, and Venice alone had dozens of opera houses, catered for by Monteverdi’s successors including Francesco Cavalli, a composer now coming back into vogue whose lurid dramas take after Poppea in combining misbehaviour in high places with seductively gorgeous music.

Cavalli's L'Egisto 1984. Photo Scottish Opera.

Opera gets national, and serious

In the second half of the 17th century opera developed along different lines in different countries. In Italy this consisted of a growing distinction between recitative and arias (as seen in the works of Cavalli), in France (at the court of Louis XIV, where opera was provided by Rameau and Lully) a highly ornate synthesis of music and dance, and in England an evolution of the traditional form of the masque, which alternated spoken episodes with musical interludes, as in Henry Purcell’s Fairy Queen, based on A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The little miracle of Dido and Aeneas (first performed some time in the 1680s, nobody is quite sure when), which might have formed the basis of a truly English operatic tradition, seems to have come and gone without anyone noticing.

Purcell's Dido and Aeneas 1978. Photo Agence de Presse Bernand.

The 18th century was dominated by singers, particularly the infamous castrati – male singers emasculated in their youth to preserve their high voices – whose combination of power, amazing vocal agility and an unearthly purity of tone (not to mention prima donna tendencies) contributed hugely to the success of opera seria. Largely drawn from classical mythology, opere serie were morality plays for European princelings, though whether they had any effect is open to question. Drama came a distant second in these costume concerts: the stagings were largely static and the only reason anyone went was to hear the vocal dynamite of the singers and catch the latest developments in theatrical machinery – as well as for the rather more important social reasons. Opera seria introduced the curious notion of the ‘exit aria’, which involves the singer leaving the stage at the end simply in order to be able to return to collect applause.

Handel goes for the heart

Handel’s operas are easily the best opere serie, and largely exempt from these criticisms: the most theatrical of composers, he epitomised the Baroque in the way he stretched boundaries while working within existing conventions. He was also instrumental in making London the operatic centre of the world, tempting the best Italian singers to join his company, and between 1711 and 1741 he wrote over 40 operas in Italian, perhaps the best known being Giulio Cesare (1724), Rodelinda (1725) and Ariodante (1735). One the most extraordinary things about Handel is how he worked largely within rigid forms to create gripping emotional dramas, the arias exploring at length the characters’ joys and (usually) sorrows: this is a very human art, bottomless in its sympathy for the world’s wretched and betrayed.

Handel's Orlando 2011. Photo Richard Campbell.

Gluck rewrites the rulES

Christoph Willibald von Gluck was opera’s first great reformer, and he reverted to an understated style of pure classicism without vocal extravagance, where the words could reassert their dramatic supremacy. His famous manifesto (written in the preface to his opera Alceste of 1766) stated his intention ‘to eliminate all those abuses which had been introduced to Italian Opera partly through the ill-advised vanity of singers and partly through the excessive complaisance of composers’. Gluck’s best known opera is another Orfeo: a simply-told but exceptionally direct story, without repetitions, that achieves its ends through a mixture of the translucent clarity of his music and a beautiful, flowing use of dance.

Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice 1979. Photo Eric Thorburn.

Anything you can do: Mozart

If nobody much actually followed Gluck’s lead, he dealt the first death-blow to opera seria and established the conditions for Mozart’s operas to be written. Mozart composed operas in all the existing traditions: opera seria (eg La clemenza di Tito, 1791), Neapolitan buffa (The Marriage of Figaro, 1786) – a form of comic drama dreamt up by playwright Carlo Goldoni and set to music by the likes of Paisiello and Cimarosa – and Singspiel (The Magic Flute, 1791), the nascent German form of operetta with long-winded and often badly written spoken dialogue (which is often rewritten for performance these days). Mozart’s revolution lay in making the music itself the prime mover of drama and character, indivisible from the words. In this he was greatly helped by having his best librettos (the words for his operas), including Don Giovanni, his greatest work, written by the reprobate Lorenzo da Ponte, a man who understood that the words of an opera need to leave room for the music to do its work.

Mozart's Seraglio 2008. Photo Drew Farrell.

After Mozart: horses for courses

Opera again began to fragment. The German Singspiel developed (and became serious-minded) through Beethoven (Fidelio, 1805) and Weber (Der Freischütz, 1821) to early Wagner (and likewise into the romantic operas of other European countries, notably Bohemia where the likes of Bedřich Smetana translated this basically comic form into such rustic romps as The Bartered Bride, 1866); the French took off in another direction with ‘Grand Opera’, a form in which spectacle and massive set-pieces were the thing, as in Gioachino Rossini’s last opera William Tell (1829). It also became obligatory to include a ballet during the course of Act II to satisfy the young bloods of the Jockey Club, who would pile into the Paris Opéra after dinner to ogle the dancers and plan their after-show assignations. Opera buffa had already been taken in hand by Rossini (The Barber of Seville, 1816), who invented the style known as bel canto – a highly flexible, rigorously trained vocal technique combining a mastery of long, smoothly sung vocal lines with lots of musical acrobatics – and also laid the foundations of the formal structures that Italian opera would adhere to for the next generation and more. This is often known as the ‘cabaletta style’, after the generally gymnastic final section of an aria, and was a flexible means of building excitement over extended periods.

Smetena's The Bartered Bride 1978. Photo Eric Thorburn.

Verdi and Wagner: blood, love and dragons

The greatest exponents of the bel canto style were Rossini’s successors, Gaetano Donizetti, composer of both the charming, tuneful and tear-jerking comedy L’elisir d’amore (1832) and the gothic tragedy Lucia di Lammermoor (1835), Vincenzo Bellini (Norma, 1831) and Giuseppe Verdi, who developed a line of romantic opera – comic and tragic – that would culminate in the bloodbaths of Verdi’s Il trovatore, Don Carlos and La forza del destino. Much of Verdi’s early work was written in a muscular version of bel canto, but he developed into a composer of great subtlety, producing works like La traviata (1853) and Aida (1871) combining romantic ardour, tragedy and social comment with a talent for providing tunes of enormous expressiveness and pathos. By the end of his life he had done away with the old individual ‘numbers’ that had made up operas to this point, and by the time of Falstaff (1893) was writing operas of virtually continuous music, the distinction between aria and recitative dissolved to a point where the terms lose their meaning. In Germany Richard Wagner was doing the same in a very different way. In his later works, The Ring (1862–76), Tristan and Isolde (1859) and Parsifal (1878), he attempted to compose what he called Gesamtkunstwerke, unified works of art where words, music, drama and staging combined seamlessly into an entirely new artform: the old Greek ideal again, in fact – plus dragons.

The basis of this is Wagner’s system of leitmotive, literally ‘leading motifs’: every character, mood, action and thing has its own musical motto. In Wagner’s imitators this can be an irritatingly parrot-like habit, but the man’s extraordinary architectural imagination, allied to an ability to do things with the orchestra that nobody had dreamed of before, created many-layered effects of huge complexity and stunning effect. It is not uncommon to hear complaints about the lack of tunes in Wagner, but this misses the point (and is also untrue). Expression purely through melody was not his thing: everything contributes. Unwilling to be associated with the fripperies of Italian opera, Wagner denied that operas were what he wrote: Parsifal was a Bühnenweihfestspiel, or ‘stage-consecration-festival-play’.

Wagner's Götterdämmerung 2003. Photo Bill Cooper.

A song of love and death: Carmen

We might often think of it as just a string of hit tunes, but Georges Bizet’s Carmen (1875) was an operatic revolution that had a huge effect on what followed. Written for the Opéra Comique in Paris – a place that specialised in unchallenging light works for the middle classes – this blood-and-guts piece for the first time put contemporary low-life (gypsies, soldiers, murderers) on stage, albeit set off with an exotic Spanish setting, and created uproar among the prim audience. Its greatest influence would be as a precursor of so-called Italian verismo (realism) which flourished with Puccini and afterwards – the slice-of-life school of opera that would more usually be intimately concerned with death.

Bizet's Carmen 2015. Photo James Glossop.

Puccini: I can make you cry

One of the great populists, Giacomo Puccini combined highly effective music with tear-jerking drama in works like La bohème (1896), Tosca (1900) and Madama Butterfly (1904) to create what most people probably still think of as the ultimate in opera. Bohème has been described as being everyone’s secret favourite opera, and in its brevity, tunefulness, general likeability and satisfactorily sad ending it certainly covers all bases. He was a terrific professional whom you could call a cynical manipulator of his audience’s emotions. But the audience is always willing to be manipulated, and Puccini is not always sufficiently appreciated for the intricate subtlety of his scores, which can get overlooked in the general razzmatazz of his big tunes and star vehicles.

Puccini’s followers developed a line of ever more lurid melodrama masquerading as realism, of which the best-known are Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci (1892) and Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana (1890), a vivid pair of one-acters often performed together and depicting the brutish, passionate lives and deaths of southern Italian peasants.

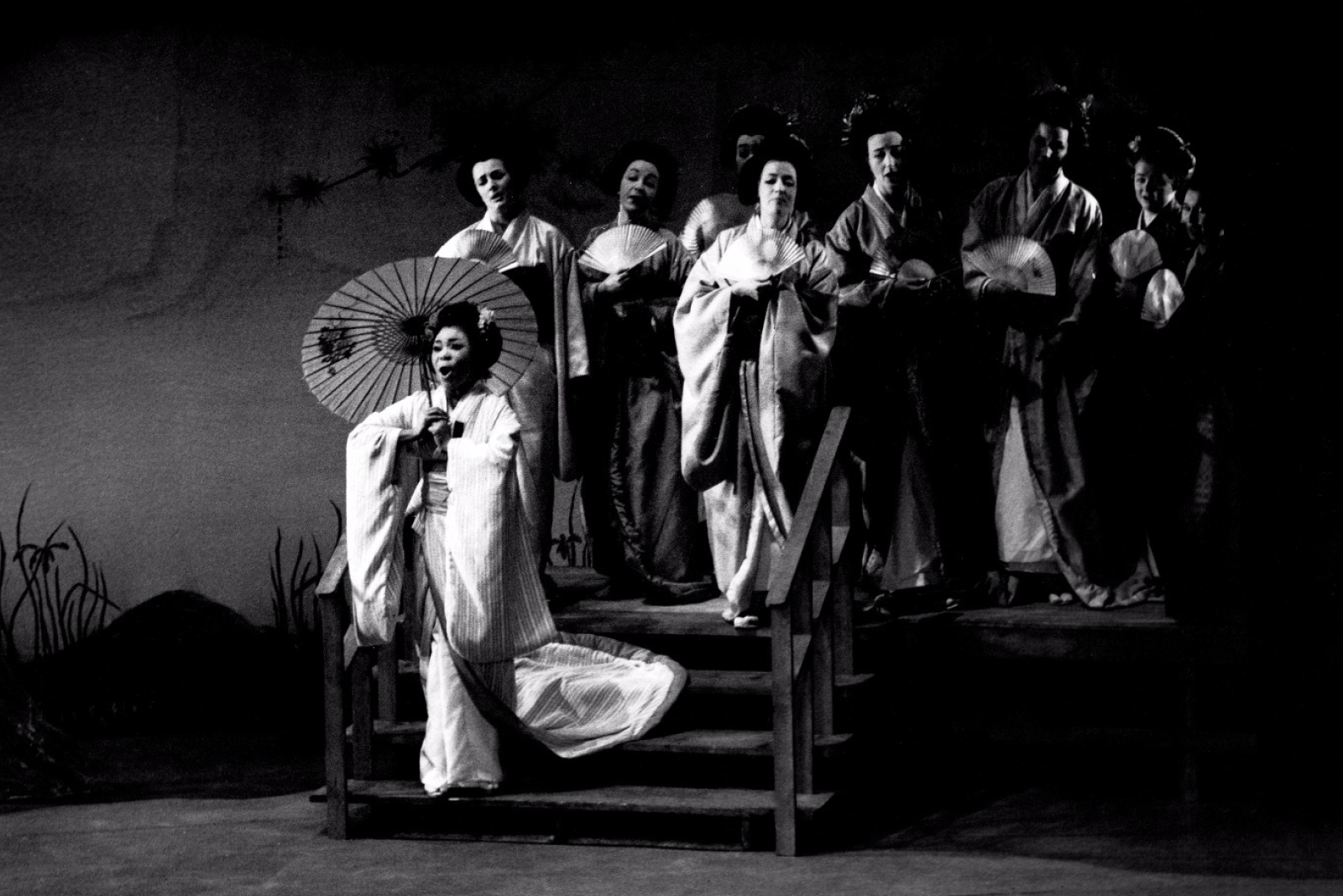

Puccini's Madama Butterfly 1965. Photo Bryan & Shear Ltd.

Doing their own thing: the 20th and 21st centuries

Wagner had taken music to the edge of apparent breakdown, and the diatonic system, based on the tension between major and minor moods, which had been flexible enough to accommodate the previous 500 years’ music, seemed on the brink of collapse. Claude Debussy and Alban Berg experimented beyond its boundaries, but opera is essentially a conservative medium, which is why Pelléas and Mélisande (1902) and Wozzeck (1925) are still in many ways the most ‘modern-sounding’ works in the repertoire. 20th-century opera is a story of composers rather than schools or styles. Richard Strauss (Der Rosenkavalier, 1911) surpassed even Wagner in staggering romanticism. Leoš Janáček and Benjamin Britten, the other indisputable colossi of the century, wrote psychodramas of great power, in entirely original musical idioms: Britten’s Peter Grimes (1945) in particular showed that it was still possible to write a popular opera in a reasonably uncompromising 20th-century idiom. George Gershwin and Leonard Bernstein factored in American music in such works as Porgy and Bess (1935) and Candide (1956). Stravinsky (in The Rake’s Progress, 1951) and Poulenc (Dialogues of the Carmelites, 1956) returned to neo-classical roots, echoing the forms and styles of Mozart and Haydn through a 20th-century prism – with different aims and results. Modern times have been dominated by the ‘minimalists’ – Philip Glass, John Adams (Nixon in China, 1987) – specialising in a kind of hypnotic, repeating, often electronic music, occasionally of great beauty and power. The Englishman Harrison Birtwistle (The Minotaur, 2008) carries the torch for the most uncompromising brand of modernism: strident, violent and discordant, this can be difficult music to appreciate, but it is undoubtedly a cogent language and Birtwistle a true composer who repays the work he asks of his audience.

Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress 2012. Photo Mark Hamliton.

Putting on my top hat: musicals

Something else rather important happened in the 20th century: the development of the musical. Its origins can be traced to the Neapolitan 18th-century buffa works of Paisiello and co., grafted onto the German Singspiel where the dialogues were spoken. 19th-century comic opera and operetta – Daniel Auber and Jacques Offenbach in France, Johann Strauss (Die Fledermaus, 1874) in Austria, Gilbert and Sullivan in England – developed this into a vastly entertaining form without social pretensions and aiming at a mass market. In the 20th century it was America that embraced the musical with gusto, helped by the fact that a lot of composers made a new home in the United States when driven out of Europe. Jerome Kern (Show Boat, 1927), Cole Porter (Kiss me, Kate, 1948), Rodgers and Hammerstein (Carousel, 1949), Kurt Weill (One Touch of Venus, 1943), Stephen Sondheim (Sweeney Todd, 1979), Leonard Bernstein (West Side Story, 1957) were the stars of the musical, and eventually Europe jumped on the bandwagon to great effect with works like Andrew Lloyd-Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar (1970) and Claude-Michel Schönberg’s Les misérables (1980).

Gilbert & Sulivan's The Mikado 2016. Photo James Glossop.

Next please

The wild diversification of styles after Wagner has actually had an exceptionally fruitful effect on musical theatre. Harrison Birtwistle’s The Minotaur has shown that despite ‘academic’ music’s exploration of the outer wilds of atonality, it can still provide gripping entertainment; Leonard Bernstein proved it is possible to marry populist styles with serious musical ambition, and composers like the Englishman Jonathan Dove (Flight, 1998, Pinocchio, 2007) continue to plough a similar furrow with considerable success.

It is true that the vast majority of the works performed around the world (not counting musicals, since the opera world is never really sure whether they should be allowed into its fold) were composed between 1781 (Mozart’s Idomeneo) and 1926 (Puccini’s Turandot). But why should that be a problem? People still look at the Elgin Marbles and Mona Lisa, still watch Shakespeare’s plays, still read Austen and Conrad. Operas are constantly reinvented in performance: every conductor, every singer, every director is dedicated to bringing the piece up as fresh as possible, and as performance and theatrical styles change over time a great deal can be revealed even about pieces we thought we knew inside out.

Operas take a long time to become accepted: 20 years ago the regular repertoire didn’t include the works of Britten, Janáček, or Poulenc; nor anything of Handel beyond Giulio Cesare. Within a generation, the operas of Mark-Antony Turnage, Gian Carlo Menotti, Peter Maxwell Davies, Harrison Birtwistle, Leonard Bernstein, John Adams, Sergei Prokofiev, and Michael Tippett will probably be as frequently performed as those of Britten are now – and Vivaldi, Lully, and Rameau will be as common as Handel. There is an immense treasure-store from the past to be excavated: of the tens of thousands of operas ever composed, only a couple of hundred are ever performed.

Since its inception, Scottish Opera has commissioned and presented new operas, among them Thea Musgrave’s Mary Queen of Scots (1978) and James MacMillan’s Inés de Castro (1996). In 2008 the Company introduced a new initiative, Five:15 Operas Made in Scotland, bringing together composers and writers working in Scotland’s creative industries to explore and develop the artform in new and exciting ways for 21st-century audiences. This culminated in a full-length collaboration between composer Stuart Macrae and novelist Louise Welsh in 2016 - The Devil Inside. In 2024, Scottish Opera's first-ever animated short opera film - Samuel Bordoli and Antonia Bain's Josefine - premieres at the Vienna Film Festival.

So opera looks both ways: to a rich past in which every possible form of music theatre has been attempted, and a future which tries to make sense of it all and to continue to explore the possibilities of the most interesting, entertaining and striving of all artistic forms.

Stuart MacRae's The Devil Inside 2016. Photo Bill Cooper.