Humperdinck

Hansel and Gretel

Programme

Engelbert Humperdinck

Hansel and Gretel

Opera in three acts by Engelbert Humperdinck

Libretto by Adelheid Wette, based on the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tale

First performed at the Hoftheater, Weimar, on 23 December 1893

Sung in English, in a translation from the German by David Pountney

Reduced orchestration by Derek Clark

Concert performance, filmed on 19 December 2020 at the Theatre Royal Glasgow

under appropriate social distancing restrictions

Welcome

Welcome to this special digital staging of Humperdinck’s captivating opera Hansel and Gretel, filmed live at the Theatre Royal Glasgow as part of our digital series Scottish Opera: On Screen.

Director Daisy Evans (whose film of Menotti’s The Telephone in 2020 gained five-star reviews) retains all the charm and fantasy of Humperdinck’s fairy-tale opera in her specially conceived concert staging, while also reimagining the story as a tale of temptation within our own consumer times, with the Witch as a purveyor of gaudy sweets and sparkling playthings that capture the attention of the two impoverished children.

We’re delighted to welcome back Kitty Whately (Hebe in HMS Pinafore) and Rhian Lois (Musetta in our outdoor La bohème last year) as Hansel and Gretel, with Scottish Opera debuts from Nadine Benjamin in the dual roles of the Mother and the Witch, and Phillip Rhodes as the Father. Former Scottish Opera Emerging Artist Charlie Drummond sings the magical roles of the Sandman and Dew Fairy.

Conductor David Parry has made many memorable appearances with Scottish Opera, and we’re pleased to welcome him back to conduct a slimmed-down version of Humperdinck’s lavish score, cleverly reduced by Scottish Opera Head of Music Derek Clark, which nonetheless retains all the opulence of the original.

We remain absolutely committed to returning to live performance as soon as we’re able to, and in the meantime, this digital concert staging has been created within current guidance from the Scottish Government. It was filmed in Glasgow on 19 December 2020, just a few hours before a new lockdown was announced.

We thank the Scottish Government for its ongoing core funding, and all of you for your continuing support and enthusiasm for the Company.

I hope you enjoy this special performance.

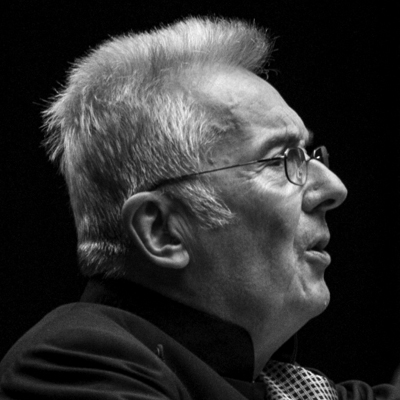

Alex Reedijk

General Director

Cast

Hansel

Kitty Whately

Gretel

Rhian Lois

The Mother/The Witch

Nadine Benjamin

The Father

Phillip Rhodes

The Sandman/The Dew Fairy

Charlie Drummond

Chorus

Barbara Cole Walton

Clíona Cassidy

Jane Monari

Sarah Shorter

The Orchestra of Scottish Opera

Creative Team

Conductor

David Parry

Staging

Daisy Evans

Film Director

Jonathan Haswell

Audio Producer

Derek Clark

Lighting Designer

Neil Foulis

Biography: ENGelBERT HUMPERDINCK

Born: Siegburg, Germany, 1854. Died: Neustrelitz, Germany, 1921

Born in the Rhine Province in western Germany, Engelbert Humperdinck began composing at the age of just seven, and, despite objections from his parents (who felt he should embark on the more serious subject of architecture), he went on to study music in Cologne and Munich with eminent figures Franz Lachner and Josef Rheinberger. Winning the first Mendelssohn Award in 1879 proved a turning point: it enabled him to travel to Italy, where he met and became friends with Richard Wagner in Naples. He later assisted the elder composer with the premiere of Parsifal at Bayreuth in 1882 (he even added a few additional bars of music to Act I to cover a scenery change) and worked as music tutor to Wagner’s son Siegfried.

Following further travels across Europe, including two years teaching at Barcelona’s Liceu Conservatoire, he became a professor at the Frankfurt Conservatoire in 1890. That same year, he began work on Hansel and Gretel, which was premiered to great acclaim in 1893 in Weimar, conducted by Richard Strauss. Humperdinck wrote six additional operas over subsequent years – including 1897’s Königskinder, the first opera to use Sprechgesang, a style of vocalisation somewhere between singing and speaking later taken up by Schoenberg and Berg – but none found the regular place in the repertoire that Hansel and Gretel achieved.

Humperdinck later taught in Boppard and Berlin, although an application to become Director of the Sydney Conservatorium of Music was scuppered by the outbreak of World War I. He also collaborated extensively with the influential theatre director Max Reinhardt, composing incidental music for several of Reinhardt’s Shakespeare productions in Berlin. Humperdinck died in 1921 following a heart attack, and the Berlin State Opera performed Hansel and Gretel in his memory a few weeks later. His name returned to a wide public consciousness in the 1960s and 70s (and again at the 2012 Eurovision Song Contest) when it was taken as the stage name of pop singer Arnold Dorsey, following a suggestion from his manager Gordon Mills, who had apparently discovered it in a music dictionary. Needless to say, the two Engelbert Humperdincks are entirely unrelated.

Synopsis

Act I – The Broom-Maker’s House

Bored and hungry, Hansel and Gretel are doing chores, but start to play to cheer themselves up. Returning home, their Mother is angry to find that they’ve abandoned their work, and accidentally knocks over a jug of milk, meaning no supper that night. Exhausted, and worried about the family’s precarious situation, she sends her children out into the forest to gather strawberries.

When the children’s Father returns, the Mother is irritated that he might have been drinking, but is overjoyed when he produces vast quantities of food. He becomes alarmed, however, when she tells him that Hansel and Gretel are in the forest, warning her that a Witch lives there. Both parents set off to look for their children.

Act II – The Forest

Happily playing and eating strawberries, Hansel and Gretel barely notice that night has fallen. They realise they’re lost, and become frightened by their voices echoing in the mist around them. But the Sandman soon appears and soothes the children with a song. Once Hansel and Gretel have said their evening prayers and fallen asleep, angels appear to protect them from harm.

Act III – The Witch’s House

At dawn, the Dew Fairy wakes Hansel and Gretel. They see a house nearby, and are excited to discover that it’s made from gingerbread, which they can’t resist nibbling. The Witch emerges and invites them inside.

When they try to run away, the Witch stops them with a spell, trapping Hansel and commanding Gretel to work. The Witch explains that Hansel isn’t yet fat enough to eat, and should be fed. She tells Gretel to help her with the cooker, but Gretel frees her brother, and both push the Witch into the oven. As she dies, previous children she had charmed come back to life. Hansel and Gretel’s parents arrive to find their children safe and happy, and the family celebrates.

Interview: Daisy Evans

Daisy Evans reveals the thinking behind her staging of Humperdinck’s fairy-tale opera

What does Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel mean to you?

I think it’s such a wonderful opera. And I also think it sometimes suffers from people assuming it’s just for children. Its music is almost Wagnerian – it has an amazingly lush orchestral score. And it’s such a charming opera, too, almost like the early Disney movies in that there’s something in it for everyone. It’s very accessible, but it also has some quite intense topics at its core.

How would you describe the opera’s themes?

There are certainly some dark elements to it. When you see Hansel and Gretel’s parents on their own, they’re really living on the breadline – the mother seems almost ready to throttle her kids, and there’s even a suggestion of domestic violence from the father. And one of my main concerns was trying to find a moral world where it’s okay for two kids to kill an old woman!

How have you gone about depicting the Witch? And how does she fit in with your overall conception of Hansel and Gretel’s world?

I thought long and hard about the best way to present the Witch, and one that wasn’t simply a get-out-of-jail, fairy-tale idea. My solution is that the family, even though they’re poor, live off the land and find a lot of joy in that. They’re very environmentally conscious, and the parents don’t want their children to have bright plastic toys, or sweets full of sugar and additives. So while the parents are trying to bring up their children in a very organic, wholesome, sustainable way, the Witch is like an explosion of gaudy plastic. She turns up with a shopping trolley full to the brim with stuff we see in pound shops, brightly coloured plastic and flashing lights. When Hansel and Gretel realise the garishness of what this actually is, they understand that this is not the life they want to lead.

What kind of mood did you have in mind for the staging?

I really wanted it to be fun and joyful, even if adults will be able to see some of the opera’s darker elements within it. With the current pandemic, everybody has had a difficult Christmas, so I wanted it to be about finding joy where we can, and about families celebrating together. And I also want it to encourage people to come back to the theatre, and to bring their children with them – to make them want to be part of this experience, and to invest in it as part of our culture.

How have you gone about bringing the opera to the stage while observing our current restrictions?

I’ve been facilitating the story being told, and making it the best experience for people watching at home. We’ve still used props and costumes, although each character has their own set of props so that they don’t share them: the kids have theirs in their backpacks, the mum has a tote bag, and the dad has a wheelbarrow. The Orchestra is at the back of the stage, and there’s a two-metre strip of what I call no man’s land between them and the singers, for safety reasons. Then we’ve created a design of connecting triangles on the stage floor, so that the performers know if they’re standing two dots away from each other in any direction, they’re safe. It’s a bit more interesting than doing social distancing in terms of lines and squares. We don’t want audience members to feel that the staging has suffered because of the restrictions – instead, we wanted to come up with an interesting theatrical way of using them.

Programme note: Hansel and Gretel

At once Wagnerian drama, psychological allegory and family treat, Humperdinck’s operatic masterpiece offers riches for all ages, as Jessica Duchen explains

Engelbert Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel started life as a family affair. The composer’s sister, Adelheid Wette, asked him to write four little choruses for her to perform with her children, setting to music verses she had written based on the famous fairy tale. The year was 1889, and Humperdinck, like so many composers of his time, was deeply in thrall to the music of Richard Wagner.

This overpowering presence was intimidating enough to composers who were not part of his circle. But for Humperdinck, who had worked with Wagner in preparations for the premiere of Parsifal and served as music tutor to his son, Siegfried, the spell was too close to home. Perhaps it was no wonder that up until then, Humperdinck had failed to find an authentic voice for his own music.

These four domestic choruses opened his floodgates. They turned out so well that Humperdinck expanded them into a Singspiel (an operetta in German with spoken episodes) with piano accompaniment, again based on Adelheid’s libretto. In 1891, he began work on a full orchestration. Two years later, the opera enjoyed its public premiere in Weimar under the baton of Richard Strauss, who promptly declared it ‘a masterpiece of the highest quality’.

The premiere’s date was 23 December 1893, and the opera has been associated with Christmas ever since, even though there’s precious little about the tale that is seasonal. With two children as its heroes, it attracts audiences of all ages – but what a terrifying story it is. Adelheid’s version softened the original, eliminating the parents’ abandonment of the children and introducing two benevolent magical figures, the Sandman and the Dew Fairy, to guard and guide the youngsters. Still, the themes of hunger, poverty and homelessness, plus the threat of abuse from a fearsome stranger, remain starkly clear and are no less disturbing, or less relevant, today.

Psychological depths

Folk tales and fairy stories have long been fine fodder for psychological interpretation. Their undeniable power is partly rooted in their sheer longevity: handed down from generation to generation over hundreds of years, they seem to become associated with deep-seated personal and collective memories. They tap strongly into psychological archetypes, while often serving, too, as cautionary tales that illustrate the alarming consequences of certain types of childish behaviour and, conversely, the advantages of qualities such as bravery and resourcefulness.

According to psychologist Bruno Bettelheim in his book The Uses of Enchantment, Hansel and Gretel illustrates the fear of starvation and warns against gluttony: ‘The story… gives body to the anxieties and learning tasks of the young child who must overcome and sublimate his primitive incorporative and hence destructive desires.’ Once the children have matured enough for their egos to triumph over their ids (or for their conscious, realistic selves to triumph over their instinctive, subconscious identities), they are released from the spell and return home to live, one hopes, happily ever after.

The story’s roots are considerably more palpable. They are sometimes traced back to the global famine of 1314, when a change in the climate led to a catastrophic failure of crops. During the mass starvation that followed, incidents of cannibalism reputedly took place in which mothers were said to have eaten their children. That’s horrific enough, but yet another theory suggests that the story was inspired by the murder of Katharina Schraderin (1618-47), known as the ‘Bakkerhexe’ or ‘baker witch’. Acquitted in the Gelnau witchcraft trial, she was then murdered by Hans and Grete Metzler and buried in their oven – for refusing to hand over her gingerbread recipe. Humperdinck’s villain, incidentally, is known as the ‘Knusperhexe’, or ‘crunchy witch’.

War and upheaval

Wilhelm and Jakob Grimm, whose version of the tale is the libretto’s chief source, were academics and cultural researchers, their work central to the Romantic movement’s surge of interest in folklore, the distant past and the supernatural. Their contemporaries and friends also included the half-siblings Clemens and Bettina Brentano and the poet Achim von Arnim (whom Bettina married), who published the folklore collections Des Knaben Wunderhorn in 1805 and 1808.

It was no coincidence that all this took place at the time of the Napoleonic Wars, when the self-proclaimed French emperor was sweeping across Europe in a chain of invasions that left millions dead and millions more uprooted, bereaved and ruined – the latter including the Grimms’ own family. Napoleon overturned the world order of 1000 years when the Holy Roman Empire fell under his influence.

Hansel and Gretel was included in the Grimms’ Kinder- und Hausmärchen (‘Children’s and Household Tales’), published in 1812 – the year Napoleon invaded Russia (as all music lovers will know from Tchaikovsky’s famous Overture). These were not children’s books, but scholarly texts, unillustrated and much annotated. The stories, abounding in starvation, cruelty and violence, were considered far from suitable for youthful readers. The Grimms published more than 200 of them between that year and 1857, in seven editions. One of their prime intentions was to conserve German folklore in an era when national identities were facing potential obliteration. These were the decades before Wagner, in The Mastersingers of Nuremberg, gave Hans Sachs his famous monologue about the need to preserve great German art when it was under threat.

Wagnerian power

Humperdinck first fell under the spell of Wagner as a student at Munich’s Royal Music School in the late 1870s. Having met the great composer in Naples, he went on to work for him at Bayreuth in 1881. The music of Hansel and Gretel could only sound more Wagnerian were it by Wagner himself – but at around 100 minutes of music, it benefits from a very un-Wagnerian concision and, at least on the surface, a direct, tuneful simplicity that makes the music instantly appealing. Some of it is based on actual German folksongs, and the flavour of that language infuses the whole opera.

Nevertheless, if folksong is the warp of the score, Wagnerian technique is the weft. Humperdinck uses leitmotifs – simple but transformable themes associated with characters or ideas – to weave the fabric of the music. These motifs can acquire a strong emotional charge as our subconscious associations build up around them. Wagner is often gloriously pre-Freudian, the most significant and transformational processes in his music happening deep under the surface, firing up the drama as if from its own subconscious realms. Humperdinck was not far behind.

The ‘Evening Prayer’ is the first idea in the opera’s Overture, so it is already comfortingly familiar by the time the children, lost in the forest, sing it together at the end of Act II – and here the music of the ‘Pantomime’ morphs it into a visionary scene that carries an astonishing spiritual power. The Witch’s music is the diametric opposite, brittle, terse and brash. The Witch herself (or even himself – the character is sometimes played by a tenor in drag) is a fabulous balance between the comic and the terrifying, all the more convincing for hiding mortal threat behind surface charm. The Father, Peter, has a distinctive ‘Rallalala’ motif, which pays dividends towards the end when the children recognise him in the distance. The Mother, Gertrude, sings wide-spun melodic lines that have more than a little in common with Wagner’s writing for Isolde or Kundry. Perhaps inspired by Wagnerian moments such as Siegfried’s Rhine Journey and the Parsifal transformation scene, the ‘Pantomime’ and the ‘Witch’s Ride’ provide two orchestral interludes at thematically opposite poles, one heavenly, the other demoniac.

Hansel and Gretel won immediate popularity, and in its first year was staged in dozens of German theatres. Ultimately, though, its composer became a victim of his own success, unable ever to match it in his other works. Humperdinck may be a one-hit wonder – but that one hit is filled with unsurpassable magic.

Author and music critic Jessica Duchen has written for the Independent, the Observer and the Sunday Times. Her most recent novel is the Beethoven-themed Immortal.

Article: Re-orchestrating Humperdinck

Scottish Opera’s Head of Music Derek Clark reveals how he transformed Hansel and Gretel’s grand orchestra into a more intimate ensemble

When Scottish Opera embarked on a tour of Hansel and Gretel to smaller venues across Scotland in 2005, my challenge was to find a way of reducing Humperdinck's large and opulent orchestra to a more manageable touring ensemble – a group that would fit in the smaller pits available at the venues where we wanted to perform.

Reducing any orchestral score is always problematic, and usually involves compromise. In the case of Hansel and Gretel, the problems are obvious: the score is noted for its wonderfully lush orchestration, and the music itself is often densely textured, so how could these aspects be replicated meaningfully with a much smaller group of players? And as for the compromise, it actually starts in the first bar of the Prelude – how to replicate the sound of four horns when you’re only allowed two? Even the light-hearted moments, such as the Dance-duet in Act I, are often full of ingenious contrapuntal musical tricks, with little motifs passing from one instrument to another in a bewildering display of compositional skill. At first I imagined that much of this musical cleverness would have to be simplified, or even cut altogether, but I soon found that removing some of the seemingly unimportant strands from the texture emasculated the music completely: it was the very complexity of the music that gave it its particular sound. This was clearly going to be trickier than I had anticipated!

The wind and brass sections Humperdinck wrote (for nine and ten players, respectively) would clearly have to be reduced. But we needed one of each instrument to cover the many solo lines, and an extra clarinet and horn for the all-important ‘middle-instrument’ textures that are such a feature of this score. The woodwind players’ ability to double on other instruments also meant that I could swap the flute for the piccolo, the oboe for the cor anglais, and the second clarinet for the bass clarinet where appropriate. (The bass clarinet, for example, along with bassoon and trombone, became part of the solution to the four-horn problem in the opening bars of the Prelude, and its darker colour, together with that of the cor anglais, was very useful in the Act II forest scene).

Pitting even this much-reduced wind and brass section (now nine players rather than 19) against a solo string quintet seemed to be asking a lot in terms of the string players’ stamina, so extra independent viola and cello parts were added, to give the possibility, where required, of a seven-part string texture. This helped particularly in the second half of the opera, where the music is sometimes incredibly dense. Even though a fuller string section is used in this performance, the seven independent parts have been maintained, so that the violas and cellos as well as the violins are divided into firsts and seconds all the way through. The violas are particularly important in this version because they can be used as either ‘lower’ violins or ‘higher’ cellos. In addition, the rich string texture available from divided violas and cellos on their own became the basis of the re-scoring of the well-known ‘Evening Prayer’ duet, where the temporary absence of the violins can be put to artistic as well as practical use.

The original harp part has been expanded and developed: because the harp has such a wide range, it can be a useful ‘binding agent’ in mixing the orchestral ingredients together. The percussion provides orchestral icing, again based very much on Humperdinck’s original. I hope the results of this re-baking will be just as sweet.

Since its first performances by Scottish Opera in 2005, this orchestral reduction has been used for several other productions by colleges (including London’s Royal Academy of Music and Manchester’s Royal Northern College of Music) and by smaller companies in both the UK and the USA. In 2019 it was used for the open-air production by English National Opera at the Regent’s Park Theatre, and most recently was also used by the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden.

Biographies

Nadine Benjamin – Mother/The Witch

Scottish Opera debut

Born in London, soprano Nadine Benjamin was a Harewood Artist at English National Opera from 2018 to 2020, and won the inaugural Fulham Opera Robert Presley Memorial Verdi Prize in 2015.

Operatic roles include: New Dark Age by Anna Meredith, Missy Mazzoli and Anna Thorvaldsdóttir (Royal Opera House Covent Garden); Clara Porgy and Bess, Musetta La bohème, Laura Luisa Miller (English National Opera); Amelia Un ballo in maschera, Ermyntrude Isabeau by Mascagni (Opera Holland Park); Desdemona Otello, title role Tosca (Everybody Can! Opera); title role Tosca, Countess The Marriage of Figaro (English Touring Opera); Nadia The Ice Break (Birmingham Opera Company); Rosalinde Die Fledermaus (Iford Arts).

She released her debut solo album, Love & Prayer, in 2018, and Emergence, a selection of songs set to the poems of Emily Dickinson, in 2019.

Clíona Cassidy – Chorus

Soprano Clíona Cassidy has sung in the chorus for Scottish Opera productions since 2012, and also sang in the Company’s educational outreach project The Opera Factory.

Scottish Opera appearances: First Bridesmaid The Marriage of Figaro.

Operatic engagements include: title role Beatrice di Tenda (Opera South); title role Alcina (Opera in the Open, Dublin); Pamina The Magic Flute (Opera by Definition); Dorabella Così fan tutte (Teatro Mancinelli Orvieto); Serafina Il campanello di notte by Donizetti (Anna Livia International Opera Festival).

She has been featured as a recording artist and songwriter on BBC Radio 3, and is also a member of the Glasgow Improvisers Orchestra.

Derek Clark – Audio Producer

Derek Clark is Scottish Opera’s Head of Music. He was born in Glasgow and studied at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama, Durham University and London Opera Centre. He joined Welsh National Opera’s music staff in 1977 as a repetiteur and staff conductor, and joined Scottish Opera as Head of Music in 1997.

Scottish Opera appearances: Samson, The Magic Flute, Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, Così fan tutte, The Barber of Seville, The Italian Girl in Algiers, The Elixir of Love, Fidelio, Rigoletto, Il trovatore, La traviata, Macbeth, Falstaff, Orpheus in the Underworld, The Pirates of Penzance, The Mikado, Carmen, Manon, La bohème, Tosca, Madama Butterfly, Eugene Onegin, Hansel and Gretel, The Burning Fiery Furnace, Inés de Castro, Five:15 (2008-10), The Lady from the Sea by Craig Armstrong – world premiere, Clemency by Sir James MacMillan – Scottish premiere, The Trial by Philip Glass – Scottish premiere. He also appeared with Jamie MacDougall in Lauder, and has devised 22 Opera

Highlights/Essential Scottish Opera programmes.

Besides his work as accompanist, coach, arranger and composer, he has assisted Sir Roger Norrington and Richard Egarr at the Edinburgh International Festival and is Musical Director of the Dundee Choral Union.

Barbara Cole Walton – Chorus

Canadian-British coloratura soprano Barbara Cole Walton was born on Vancouver Island, and attended the University of Victoria before moving to Glasgow to study on the opera course at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland.

Scottish Opera appearances: Shepherd Boy Tosca, Ice Anthropocene (cover), Controller Flight (cover), Naiad/Echo Ariadne auf Naxos (cover).

Operatic engagements include: Blonde Die Entführung aus dem Serail (Diva Opera); Queen of the Night The Magic Flute (ENO Baylis Youth Project); Norina Don Pasquale (Wexford Opera ShortWork); Baucis Philemon and Baucis (Bampton Classical Opera); Amarilli Il pastor fido (New Chamber Opera).

Charlie Drummond – The Sandman/The Dew Fairy

Born in Lincoln, Charlie Drummond studied at King’s College London, the Opera School at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland and the National Opera Studio. She is also a Samling Young Artist, and was a Scottish Opera Emerging Artist 2019/20.

Scottish Opera appearances: Opera Highlights Autumn 2019, Dhia Iris, Belle The Narcissistic Fish, Fiordiligi Così fan tutte.

Operatic engagements include: title role (cover) Anna Bolena (Longborough Festival Opera); Donna Anna Don Giovanni (British Youth Opera); Rosalinde Die Fledermaus, Fiordiligi, Countess The Marriage of Figaro, Mrs Julian Owen Wingrave, Eleonora Prima la musica e poi le parole by Salieri (RCS); Sofia Il signor Bruschino (Raucous Rossini); Serena Farage The Secretary Turned CEO by Danyal Dhondy – world premiere (Lucid Arts); Voice Simoon by Erik Chisholm – world premiere (Music Co-OPERAtive Scotland).

Daisy Evans – Staging

Daisy Evans works internationally as a director in theatre, opera and film. She is Artistic Director of Silent Opera, as well as a freelance writer and librettist.

Scottish Opera appearances as director: The Telephone, Opera Highlights Autumn 2018.

Directing credits include: Don Pasquale (Welsh National Opera); La bohème (Hampstead Garden Opera); La traviata (Longborough Festival Opera); Così fan tutte (Bury Court Opera); The Cunning Little Vixen (Silent Opera/English National Opera); The Fairy Queen, King Arthur (Barbican/Academy of Ancient Music); Giovanni (Silent Opera/Beijing Music Festival); A Garden Dream, Wakening Shadow (Glyndebourne); Falstaff (Grimeborn Festival, Wilton’s Music Hall); Shopera: Carmen (Royal Opera House Covent Garden); The Bear, A Dinner Engagement (Royal Academy of Music); L’incoronazione di Poppea (Snape Proms); L’Orfeo (Silent Opera).

Her opera librettos include new translations and interpretations of The Cunning Little Vixen, Don Giovanni and Don Pasquale.

Neil Foulis – Lighting Designer

Neil Foulis has worked in the entertainment industry since graduating from the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland in 2013. In his initial freelance career, he undertook a variety of roles in mid- and small-scale theatre across Scotland. He returned to Glasgow in 2018 to take up his current role as Lighting Programmer at Scottish Opera, where he has worked on productions including The Magic Flute and Nixon in China, as well as Così fan tutte in concert.

Among the other productions and events he has lit are The Island (National Youth Theatre at Platform); Purposeless Movements (Birds of Paradise Theatre Company); MoonWalk Scotland (Hawthorn Theatrical); Oklahoma! (Curve Young Company); Legally Blonde (Glasgow Kelvin College); Fiddler on the Roof (Curve Young and Community Company). He has also worked on several projects at the RCS and Platform in Glasgow.

Jonathan Haswell – Film Director

Jonathan Haswell is a multi-camera director and producer of live music, theatre and other events for television, DVD, cinema and online. He worked in the classical music department of BBC Television for nearly 20 years, and since 2013 has worked for a variety of producers, independent companies and institutions. Among the recent productions and other events he has filmed are The Tales of Hoffmann, Norma, Werther, The Importance of Being Earnest and Boris Godunov (The Royal Opera Live); World Ballet Day (Royal Ballet); and Somme 100, Battle of Britain 75 Memorial Service and VJ Memorial Day (BBC Television). He recently directed Scottish Opera’s film of Così fan tutte, as well as the film of Anthropocene in 2019.

Rhian Lois – Gretel

Welsh soprano Rhian Lois studied at Cardiff’s Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, and at London’s Royal College of Music and National Opera Studio.

Scottish Opera appearance: Musetta La bohème.

Operatic engagements include: Papagena The Magic Flute, The Intelligence Park by Gerald Barry (Royal Opera House Covent Garden); Zerlina Don Giovanni (Santa Fe Opera); Nannetta Falstaff (The Grange Festival); Adele Die Fledermaus, Nerine Medea by Charpentier, Valencienne The Merry Widow, Susanna The Marriage of Figaro, Governess The Turn of the Screw, Atalanta Xerxes, Frasquita Carmen, Young Woman Between Worlds by Tansy Davies, First Niece Peter Grimes, Yvette The Passenger by Weinberg, Musetta, Papagena (English National Opera); Where the Wild Things Are by Oliver Knussen (Mariinsky Concert Hall, Alexandra Palace with Shadwell Opera); Angelika Figaro Gets a Divorce by Elena Langer (Grand Théâtre de Genève); Adele Die Fledermaus (Welsh National Opera); Pamina The Magic Flute (Nevill Holt Opera); Eurydice Orpheus by Telemann (Classical Opera).

Anthony Moffat – Leader, The Orchestra of Scottish Opera

Born in the Borders, Anthony Moffat trained at London’s Royal Academy of Music with the Armenian soloist and leader Manoug Parikian. As a member of the Da Vinci Trio, he has toured Scotland and appeared on BBC Radio 3. His career as orchestra leader began when he became co-leader of the Hallé, and he took up the post of Leader of The Orchestra of Scottish Opera in 2000. He has appeared as guest leader at Opera North, and with the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, BBC Concert Orchestra, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland and the Orchestra of Welsh National Opera. He has also been invited to guest lead the BBC Symphony Orchestra. He plays a fine Italian violin made in 1695 by Giovanni Grancino.

Jane Monari – Chorus

Born in Philadelphia, mezzo-soprano Jane Monari studied at New York’s Juilliard School and London’s Royal Academy of Music, before moving to Scotland to study at the Alexander Gibson Opera School at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland.

Scottish Opera appearance: Page Rigoletto.

Operatic engagements include: Suzuki Madama Butterfly (OperaUpClose); title role Carmen (Opera at the King’s Head); Tasse chinoise L’enfant et les sortilèges (VOPERA).

David Parry – Conductor

David Parry works across a wide range of opera, concert and symphonic music.

Scottish Opera appearances as conductor: Carmen, The Silken Ladder, La traviata, Susanna’s Secret, Zanetto.

Operatic engagements include: The Adventures of Pinocchio by Jonathan Dove – world premiere (Opera North/Stuttgart State Theatre); The Flying Dutchman (Portland Opera); Madama Butterfly (English National Opera); Così fan tutte, Flight – world premiere (Glyndebourne); Mary Stuart (Royal Swedish Opera); The Tales of Hoffmann (Wuppertal Opera House); Moses in Egypt (Cologne Opera); Mansfield Park by Jonathan Dove (The Grange Festival); The Barber of Seville (Basel Theatre); Tosca (Dutch Touring Opera); Marx in London by Jonathan Dove – world premiere (Bonn Theatre).

He has appeared frequently on the concert platform with orchestras including the London Philharmonic, Philharmonia, BBC Symphony, Royal Philharmonic, Hallé, Bournemouth Symphony, City of Birmingham and English Chamber orchestras. His discography includes many recordings for Chandos and Opera Rara. His recording of Rossini’s Ermione won a Gramophone Award for best opera in 2011.

Phillip Rhodes – Father

Scottish Opera debut

New Zealand-born, UK-based baritone Phillip Rhodes studied at the Cardiff International Academy of Voice under Dennis O’Neill, and was an emerging artist with New Zealand Opera.

Operatic engagements include: Escamillo Carmen (Welsh National Opera, Royal Opera House Covent Garden, The Grange Festival); Speaker The Magic Flute (Welsh National Opera); Figaro The Marriage of Figaro, Alfio Cavalleria rusticana, Silvio Pagliacci, Renato Un ballo in maschera, Mizgir The Snow Maiden, Marcello La bohème, Father (Opera North); Scarpia Tosca (Dutch Touring Opera); Enrico Lucia di Lammermoor (Auckland Opera Studio); Older Man Between Worlds by Tansy Davies – world premiere (English National Opera); Count di Luna Il trovatore, Scarpia (Dorset Opera Festival); Monterone Rigoletto (New Zealand Opera); title role Hohepa by Jenny McLeod (New Zealand Festival of the Arts).

Sarah Shorter – Chorus

Mezzo-soprano Sarah Shorter is based in Glasgow.

Scottish Opera appearances: Boletta Lady from the Sea by Craig Armstrong – world premiere, Lady in Waiting/Second Witch Macbeth, Giovanna Rigoletto (cover), Flora La traviata (cover), Peep-Bo The Mikado (cover), Kitchen Boy Rusalka (cover), Mercedes Carmen (cover).

Operatic engagements include: Julia Bertram Mansfield Park by Jonathan Dove (Opera South).

She has also toured with the Scottish Opera Education project The Opera Factory, and is a founder member of the a cappella group The All Sorts.

Susannah Wapshott – Chorus Master

Susannah Wapshott is Associate Chorus Master and a repetiteur at Scottish Opera. She studied at Manchester University, the Royal Northern College of Music and the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama, winning several prizes for accompanists and repetiteurs. She made her conducting debut in 2009 with Orff’s Carmina Burana at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.

She has worked for Scottish Opera since 2008 on more than 50 productions, including as Assistant Conductor for Nixon in China, Kátya Kabanová, Greek, The Trial, Orfeo ed Euridice and Macbeth, and Music Director from the piano for small-scale tours of Carmen, La traviata, Rodelinda and Macbeth. She has conducted Scottish Opera Unwrapped for Orfeo ed Euridice and Nixon in China. Between 2014 and 2017, Susannah was Music Director of Edinburgh Grand Opera, conducting The Pilgrim’s Progress, L’elisir d’amore and La bohème, and she is currently Music Director of the Helensburgh Oratorio Choir. She is a Dallas Opera Conducting Fellow for 2021-22.

Kitty Whately – Hansel

Mezzo-soprano Kitty Whately studied at Chetham’s School of Music and at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama and Royal College of Music International Opera School. She has won the Kathleen Ferrier Award and the Royal Overseas League Award for singers, and was a BBC New Generation Artist.

Scottish Opera appearance: Hebe HMS Pinafore.

Operatic engagements include: Isabella Wuthering Heights by Bernard Hermann, Kate Owen Wingrave (Opéra national de Lorraine, Nancy); Paquette Candide (Bergen National Opera); Mother/Other Mother Coraline by Mark-Anthony Turnage (Royal Opera House at the Barbican); Dorabella Così fan tutte, Rosina The Barber of Seville, Stewardess Flight (Opera Holland Park); Nancy Albert Herring (The Grange Festival); Hermia A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Aix-en-Provence Festival, Beijing Music Festival, Bergen National Opera); Dorabella (English Touring Opera).

She has recorded two solo albums, This Other Eden and Nights not spent alone, the second of which features a song cycle written for her by Jonathan Dove.

The Orchestra of Scottish Opera

Leader Anthony Moffat

First Violins

Anthony Moffat

Frances Pryce †

Katie Hull § †

Terez Korondi

Timothy Ewart

Sharon Haslam

Sian Holding

Michael Larkin

Gemma O’Keeffe

Second Violins

Angus Ramsay * †

Giulia Bizzi

Liz Reeves

John Robinson

Helena Zambrano Quispe

Malcolm Ross

Maria Oguren

Violas

Lev Atlas * †

Rachel Davis

Mary Ward

Shelagh McKail

Alison Hastie

Ian Swift

Cellos

Martin Storey *

Marie Connell

Sarah Harrington

Aline Gow

Double Basses

Peter Fry *

Tom Berry †

Christopher Freeman

Flute/Piccolo

June Scott **

Oboe/Cor Anglais

Amy Turner * †

Clarinets

Nicholas Ross *

Lawrence Gill †

Bass Clarinet

Lawrence Gill †

Bassoon

Janet Bloxwich * †

French Horns

Sue Baxendale * †

David Pryce

Ian Smith

Trumpet

Paul Bosworth *

Trombone

Cillian Ó Ceallacháin *

Bass Trombone

Christopher Stearn †

Timpani

Ruari Donaldson * †

Percussion

Jay Allen *

Harp

Saida de Lyon *

§ Assistant Leader

* Section Principal

** Guest Section Principal

† Visiting Tutor to the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland

Orchestra Coordinator

Heather North

Orchestra Technical Coordinator

Barry Inglis

Orchestra Technicians

Brian Murphy

Noel Mann

Production Team

Assistant Conductor

Derek Clark

Music Librarian

Gordon Grant

Repetiteurs

Fiona MacSherry

Susannah Wapshott

Chorus Master

Susannah Wapshott

Production Manager

Amy Wilson

Company Manager

Lynn Tonner

Deputy Company Manager

Kenny Boyd

Head of Wardrobe

Lorna Price

Costume Supervisor

Beth Hicks

Costume Cutter

Yolanda Brook

Costume Assistant

Polly Russell

Wardrobe Mistress

Gloria del Monte

Deputy Wardrobe Mistress

Emma Butchart

Hair & Make-up Supervisor

Alison Chalmers

Hair & Make-up Assistants

Natalie Hargreaves

Kerrie Scullion

Head of Electrics

Robert B Dickson

Lighting Supervisor & Lighting Programmer

Neil Foulis

Electrics & Audio Visual Chargehand

Barry McDonald

Electrics Chargehand

Andrew Burnside

Props Supervisor

Marian Colquhoun

Prop Makers

Nicole Green

Aimee Moorhead

Running Props Supervisor

Katie Todd

Head of Stage

Ben Howell

Assistant Head of Stage

Martin Woolley

Stage Wingman

Stephen Fulton

Stage Manager

John Duncan

Deputy Stage Manager

Donald Ross

Assistant Stage Managers

Kieron Johnson

Marian Sharkey

Vision Mixer & Script Supervisor

Gemma Dixon

Engineering Manager

Gareth Gordon

Vision Engineer

Kerry Gordon

Film Editor

Antonia Bain

Audio Engineer

Cameron Crosby

Audio Chargehand

Rebecca Coull

Camera Supervisor

Andy Parr

Camera Operators

Chris Flint

Des O’Hare

Niall Preston

Rigger/Camera Assistant

Kostas Giamarelos

Rigger/Driver

Stephen McNally

Rig Assistant

Molly Gillon

Audio Describer

Jonathan Penny

Photographer

James Glossop

With thanks to everyone in the Scottish Opera team involved in making this production: our full staff listing is here.

Our sincere thanks also go to all the staff and management at the Theatre Royal Glasgow for their kind support.

Scottish Opera

General Director

Alex Reedijk

Music Director

Stuart Stratford

Orchestra & Concerts Director

Jay Allen

Head of Music

Derek Clark

Director of Outreach & Education

Jane Davidson

Head of Casting

Sarah-Jane Davies

Director of Marketing & Communications

Caroline Dooley

Director of Fundraising

Kirsten Howie

Director of Finance

Judith Patrickson

Human Resources Manager

Catherine Shaw

Technical Director

Andrew Storer

Director of Planning

Vivienne Wood

Support us

If you’ve enjoyed this production of Hansel & Gretel, and this digital programme, please help us to create the next Scottish Opera production by donating online today.